The British Army’s Occupation of Northwest Germany after May 1945

After the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945, the victorious Allied powers divided the country into four occupation zones, each controlled by one of the four occupying powers - the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. This division of Germany would mark the beginning of a new era for the country, as it faced a long and difficult process of reconstruction and democratization. In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

The British Occupation of Germany after May 1945

On 25 August 1945, Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group was renamed the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). It was responsible for the occupation and administration of the British Zone in northwest Germany, including the cities of Hamburg and Bremen, assisted by the Control Commission Germany (CCG). The CCG took over aspects of local government, policing, housing and transport.

Their primary objective was to demilitarize and disarm the defeated German forces, as well as to dismantle the Nazi regime and bring war criminals to justice. The British forces, under the command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, faced a daunting task, as Germany was in a state of complete chaos and disarray.

One of the first challenges the British faced was dealing with the large numbers of displaced persons, refugees, and prisoners of war. The British Army, along with other Allied powers, established numerous displaced persons camps and worked to repatriate prisoners of war and refugees to their home countries. The British also faced the challenge of providing food and shelter to the German population, which was suffering from severe shortages of basic necessities such as food, fuel, and medicine. The BAOR mobilised former enemy soldiers into the German Civil Labour Organisation (GCLO), providing paid work and accommodation for over 50,000 Germans by late 1947.

The BAOR was also responsible for pursuing suspected war criminals in its zone of occupation. It established the British Army War Crimes Investigation Teams (WCIT) and was assisted by other units, including the Special Air Service (SAS). The most famous Nazi caught by the British was Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. He was arrested at a checkpoint and taken to an interrogation camp near Lüneburg. However, Himmler was able to escape prosecution for his crimes by committing suicide with a concealed cyanide pill. Political support for war crimes prosecutions soon declined as relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated. It soon became a political necessity for the Western powers to make friends with the Germans rather than prosecute them.

The British Sector of Berlin 1945

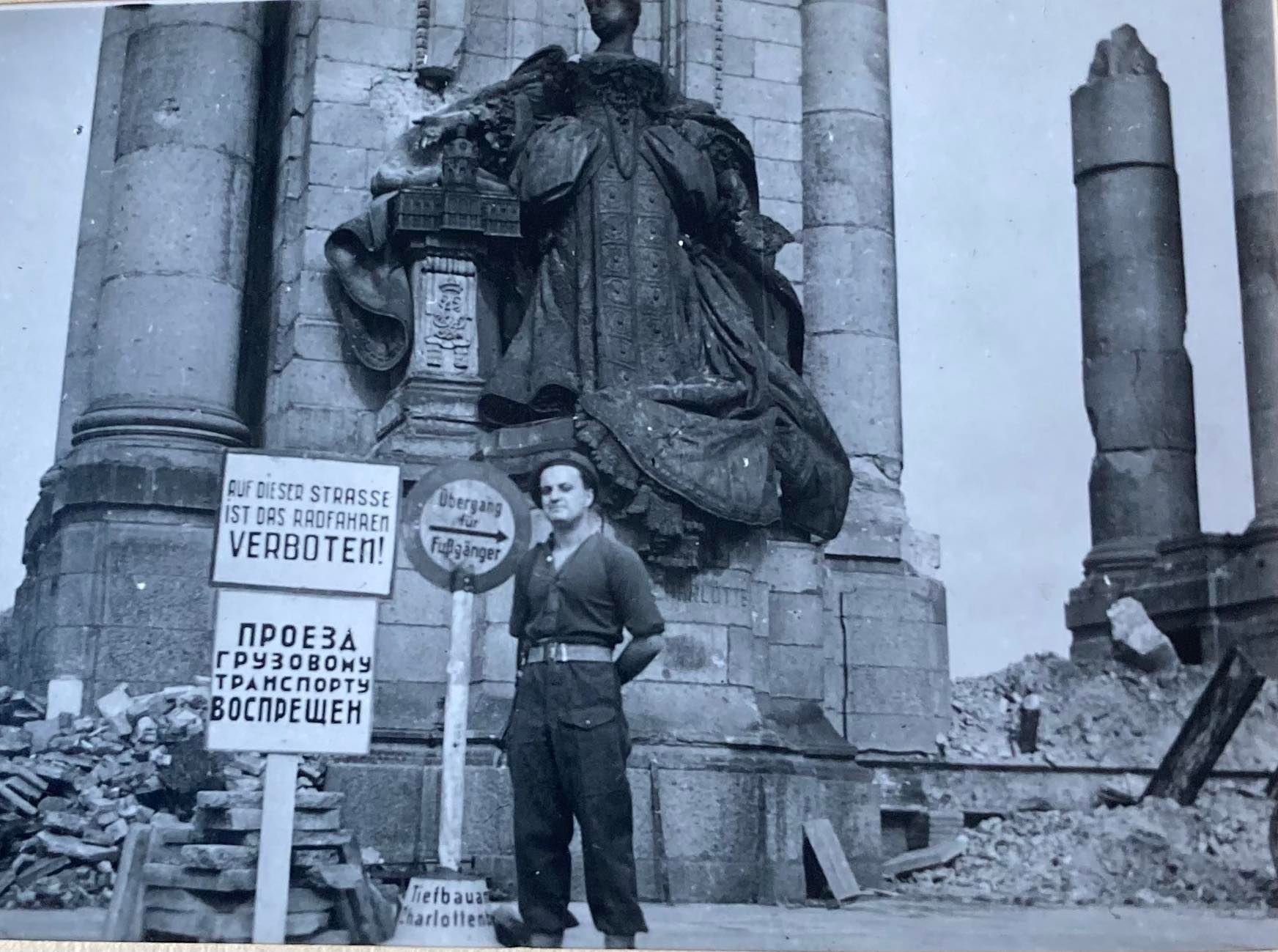

The British Army's occupation of the British sector of Berlin in 1945 was a key moment in the post-war history of Germany. Berlin, which was located deep within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, was divided into four sectors, with the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, and France each controlling a sector. The British sector was in the western part of the city.

The British Army faced numerous challenges in the occupation of Berlin. The city had been heavily bombed during the war, and many buildings were in ruins. The British Army worked to rebuild the city's infrastructure and provide basic services such as water, electricity, and sanitation.

Another major challenge faced by the British Army was dealing with the Soviet Red Army, which was stationed in and around Berlin. The relationship between the British and the Soviets was strained, with tensions running high over issues such as the repatriation of Soviet prisoners of war and the control of Berlin. The British Army, along with the other Allied powers, worked to maintain a delicate balance of power in the city, while also providing security and maintaining order.

The Victory Parade of July 1945

On 21 July 1945, the British held a victory parade through the ruins of Berlin to commemorate and celebrate the end of the Second World War. Around 10,000 troops of the British 7th Armoured Division, the famous 'Desert Rats', were paraded under review by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. On 7 September 1945, there was another parade featuring all the victorious Allies, but neither Montgomery nor U.S. General Dwight D Eisenhower attended. This gesture signified a deterioration in the relationship between the Allies, as differences in ideology between the West and the Soviet Union were becoming harder to ignore and the slide towards a Cold War had begun.

British Pathe News footage of the Berlin Victory Parade, 21 July 1945.

An Iron Curtain

Relations between the Western powers and the Soviet Union deteriorated immediately following the end of the war in Europe. The main sources of tension were the Soviet Union's unwillingness to allow democratic governments to emerge in Eastern Europe, and its desire to maintain a sphere of influence in the region. The Western powers, led by the United States, saw this as a threat to their own security and interests.

The Soviet Union's aggressive actions in the post-war period, including the establishment of communist governments in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, fuelled Western fears of Soviet expansionism. The United States responded by implementing the Truman Doctrine, which committed the U.S. to support countries threatened by communism, and by providing economic and military aid to Western Europe through the Marshall Plan.

Tensions between the West and the Soviet Union reached a boiling point in 1947 when the Soviet Union refused to participate in the Marshall Plan and instead formed its own economic bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). In 1948, the Soviet Union blockaded Berlin, prompting the Western powers to launch the Berlin Airlift to supply the city.

On March 5, 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. In this speech, Churchill warned of the growing Soviet threat in Europe and called for a closer alliance between the United States and Great Britain to contain Soviet aggression. The speech marked a turning point in the post-war era and is considered a seminal moment in the Cold War.

In 1949, the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). In 1955, West Germany joined NATO and was encouraged to build a new military, the Bundeswehr. In response, the Communist states of Eastern Europe formed the Warsaw Pact.

Sources:

Photography/Images:

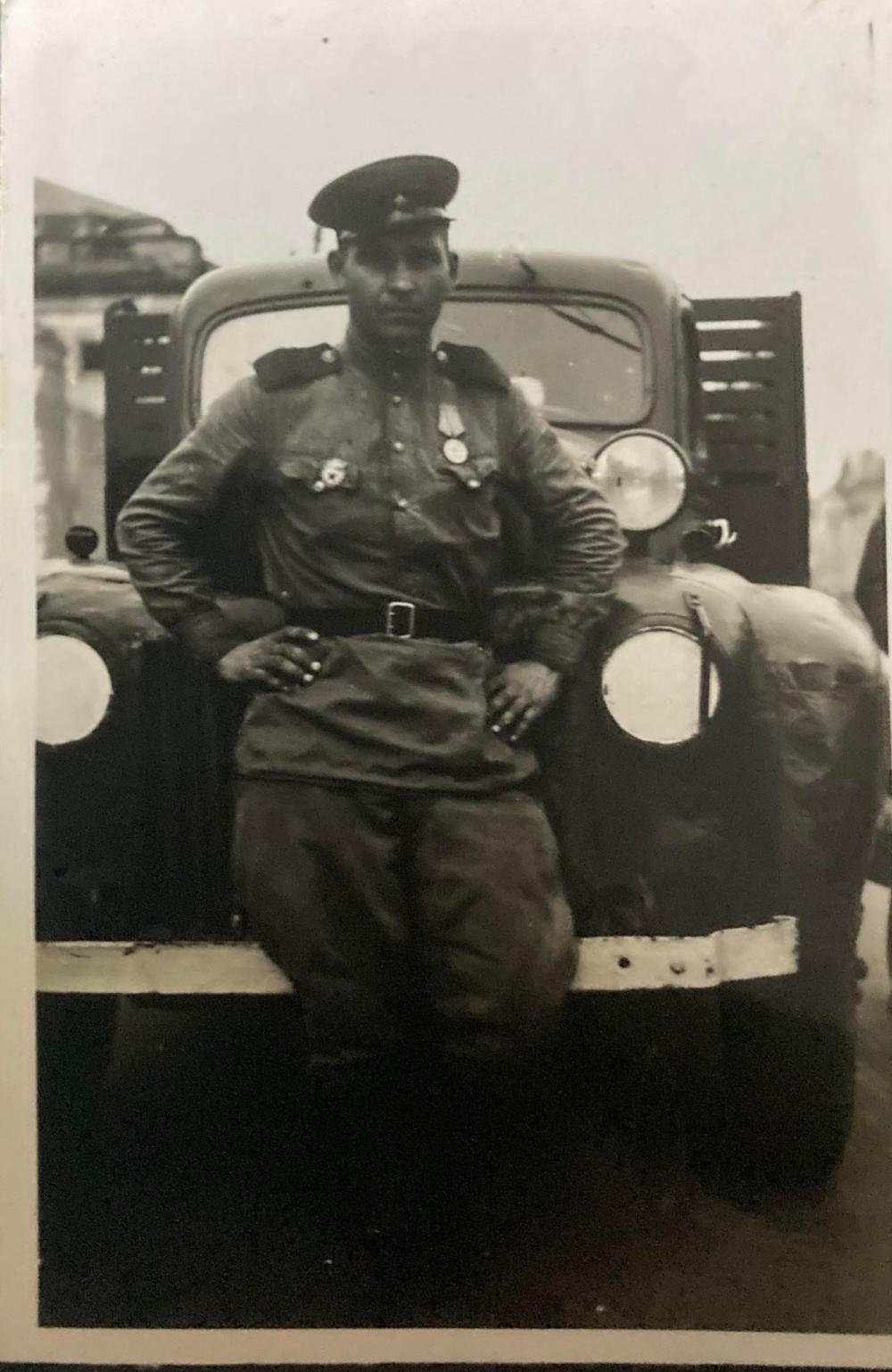

All photographs used to illustrate this article were taken by my relative George Trumpess who was stationed in Minden, Germany, and travelled regularly to Berlin during the summer of 1945.