Blog

The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage, people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We want to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. We also look at the history of unique World War II artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

Death and Taxes: Financing Britain’s Wars

Ever wondered why we pay taxes the way we do? Our latest guest blog post uncovers the fascinating wartime origins of the UK tax system.

In this intriguing exploration of British fiscal history, Simon Thomas, Managing Director of Ridgefield Consulting, reveals some of the surprising and intricate relationships between warfare and taxation in the United Kingdom. From medieval scutage to the modern PAYE system, this article reveals how moments of national crisis fundamentally shaped the tax structures we know today. Thomas takes us on a journey through centuries of innovation in public finance, showing how creative solutions to wartime funding challenges evolved into the cornerstone principles of modern taxation. Whether you're a history enthusiast, a tax professional, or simply someone who is curious about how our current system came about, this article offers valuable insights into how national emergencies have consistently driven financial innovation in Britain.

You may wonder what war and taxes have in common. Unbeknownst to many, the two have strong links throughout UK history. Wars, often expensive and prolonged, have frequently driven the Government and historically the Crown to seek new ways to generate revenue through the rise of existing taxes and the introduction of new taxes. Over the centuries, the burden of financing these conflicts has shaped the UK’s modern-day taxation system.

Early Taxation and War

The roots and early intertwining of taxation and war begin in medieval times. In tumultuous Norman England, Henry I often gifted land to his knights or nobles under the ‘feudal system’. In return he expected them to offer their military service, and this was central to supporting and building his military.

If these landholders did not want to offer their service in exchange for the land, they could pay a tax called ‘scutage’ and the King would use this money to hire professional soldiers in their place. This practice became a vital source of funding in war and the Crusades and was adopted further by Henry II.

The Window Tax and Creative Revenue Measures

Over the centuries, financial pressures from ongoing wars pushed the government to come up with creative, controversial, and sometimes unusual, forms of taxation. One famous example was the window tax, introduced in 1696 under William III. This tax was designed as an indirect method to tax wealthier households without imposing a formal income tax. Homeowners were taxed based on the number of windows in their homes, as larger homes with more windows were often owned by the wealthier classes. However, to avoid the tax, many property owners began bricking up their windows, giving rise to the term “daylight robbery.”

Other unique taxes have followed in history, like the hearth tax, which charged per fireplace, and the hair powder tax, imposed on those who wore powdered wigs—a symbol of wealth at the time. These inventive taxes highlight how the government’s need for revenue during times of crisis arose. Many of these policies, despite their unusual nature, set the foundation for modern progressive taxes.

The Napoleonic Wars: Income and Inheritance Tax

The Napoleonic wars (1799-1815) marked a turning point in taxation and, to finance its immense costs, Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger introduced income tax in 1799. This was the first taxation of its kind on personal earnings and, even though it was originally meant as a temporary measure, set the stage for modern taxation.

The birth of inheritance tax was brought in initially known as ‘legacy duty’ under George III's reign, a tax was imposed on property passed through wills to raise revenue for the government. Legacy tax was levied on how close the relationship of those who inherited was to the deceased. This tax later evolved in the late 1800s as the wars needed more revenue and saw the introduction of succession duty which would tax the whole of the inherited state like today's form of inheritance tax.

The World Wars and Expansion of the Tax System

War is expensive for all; however, the government realized that some industries were profiting from ongoing troubles, for instance, arms manufacturers. During the First World War (1914-1918), because of this, they introduced an excess profits tax on profits that were above their normal pre-war level. This tax was levied at 50% on the profits that surpassed the normal level, with a £200 deduction per year for each business.

The Second World War (1939-1945) saw an expansion of these wartime taxes, with significant increases in income tax and other goods and services, to help raise the money needed to support the war effort. In 1938 they decided to increase income tax, the standard rate was increased to (27.5%) 5 shillings and 6 pence.

Additionally, a surtax, like today's additional tax bracket, was introduced: incomes over £50,000 were subject to a 41% surtax on top of the standard rate, meaning income below £50,000 was taxed at 27.5%, and any income above this threshold faced the higher surtax rate.

To streamline tax collection, the PAYE (Pay As You Earn) system was introduced in 1944 and now some 10 million people are paying direct taxation. This system allowed employers to deduct income tax directly from employees’ wages on a weekly or monthly basis, making tax collection more efficient and forming the basis of the modern income tax system.

Recovering from World War II, the government faced the financial challenge of rebuilding the country, leading to further increases in taxes, particularly inheritance tax. Rates soared from below 60% to as high as 80% by 1969, which is a stark contrast to today's rate of 40%.

In summary, the history of taxes has always been intertwined with wars in the UK and shows how taxation has often been a balancing act between government goals and public needs. These taxes, originally meant to be temporary, have become a lasting part of today’s system, reminding us of how times of crisis can shape what society expects from taxation.

About the Author

Simon Thomas, Managing Director of Ridgefield Consulting. Simon has a longstanding background in tax and accounting, starting with his father, Brian Thomas, who is a Chartered Accountant. Simon trained in London, at one of the Big4 – EY, where he gained expert knowledge and experience. Simon started Ridgefield Consulting in 2010. In April 2021, he expanded the business by acquiring a sister practice Kench & Co.

Sources:

J.R.T. Hughes, Financing the British War Effort, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Steven A. Bank & Kirk J. Stark, War & Taxes, Journal of Scholarly Perspectives, 2008

From Battlefields to Boardrooms: How World War II Tactics Can Revolutionise Your Business Strategy

In our latest article, we delve into the contrasting tactics used by the British and German armies during WWII and extract practical advice for today’s business leaders. Discover how the British Army’s centralised command structure often led to slower response times and missed opportunities, and learn how you can avoid these pitfalls in your own organisation.

A Light Tank Mk.VIA of the 3rd King's Own Hussars. By British Army photographer. - This photograph ARMY TRAINING comes from the collections of the Imperial War Museums (collection no. 4700-101), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2113928

In the high-stakes arena of modern business, leaders are constantly seeking innovative ways to stay ahead of the competition. Surprisingly, some of the most valuable lessons in organisational agility and decision-making can be drawn from an unexpected source: Second World War military tactics. In this article, we will briefly explore the contrasting tactics used by the British and German armies in WWII and provide some practical advice for today's business leaders.

The British Approach: Centralised Command and Its Pitfalls

During World War II, the British and German armies employed starkly different tactical approaches, which had significant impacts on their battlefield effectiveness. The British Army, particularly its infantry, often found itself at a disadvantage due to its rigid command structure. This system was characterised by centralised decision-making, strict adherence to hierarchy, and limited autonomy for lower-ranking officers and soldiers.

As a result, British units frequently had to await orders from higher up the chain of command before adapting to new situations. This led to slower response times, missed opportunities, and loss of initiative on the battlefield. The inflexibility of the British system often left them struggling to keep pace with rapidly changing circumstances.

The German Strategy: Auftragstaktik and Decentralised Decision-Making

In contrast, the German army embraced a philosophy known as “Auftragstaktik” or mission-type tactics. Decentralised decision-making and empowerment of junior officers and non-commissioned officers marked this approach. It allowed for greater flexibility to adapt to changing battlefield conditions.

The German approach fostered initiative and adaptability at all levels, enabling their forces to react quickly to evolving threats and exploit unexpected weaknesses. This agility gave them a significant advantage in maintaining a high level of operational tempo and seizing opportunities as they arose.

StuG´s of the SS-Kampfgruppe “Harzer” of the 9th SS-Panzer-Division “Hohenstaufen” during the battle of Arnhem, Operation Market Garden 1944.

In Aaron Bates’ book, The Last German Victory (2021) he highlights the stark contrast between German and British military tactics during the ill-fated Operation Market Garden of September 1944. The German army’s doctrine emphasised individual initiative and aggression, allowing their forces to quickly adapt and respond to unexpected situations. This approach, coupled with their reliance on self-contained infantry units with substantial organic firepower, provided a significant tactical advantage. In contrast, the British Army’s strategy was heavily dependent on indirect firepower (artillery) and rigid planning, which proved less effective in the fast-paced, airborne assault environment of Market Garden. Bates argues that these doctrinal differences were pivotal in shaping the battle’s outcome, displaying the Germans’ ability to leverage their strengths against the Allies’ more rigid and less adaptable tactics.

StuG´s of the SS-Kampfgruppe “Harzer” of the 9th SS-Panzer-Division “Hohenstaufen” with British prisoners during the battle of Arnhem, Operation Market Garden 1944.

Translating Military Tactics to Business Strategy

The historical example of these contrasting military tactics holds valuable lessons for today's business leaders. Companies that allow employees to make decisions within the framework of overall organisational goals are likely to be more agile and responsive to market changes. Encouraging initiative at all levels can lead to innovation and improved problem-solving.

A decentralised approach can significantly reduce the time it takes to react to new challenges or opportunities. In a fast-paced business environment, the ability to quickly adapt to changing circumstances is crucial for success. While maintaining strategic oversight is important, creating a culture of empowerment allows for better tactical execution.

Implementing Mission-Type Tactics in the Corporate World

Clear Communication of Goals

To apply these lessons in a business context, leaders should focus on clear communication of goals. It is essential that all employees understand the company’s overall mission and objectives. This shared understanding provides a framework within which individuals can make decisions confidently.

Trust and Empowerment

Trusting and empowering employees is crucial. Micromanaging employees can stifle creativity, erode trust, and lead to decreased productivity and job satisfaction, ultimately resulting in higher turnover rates and a toxic work environment. Give team members the authority to make decisions within their areas of responsibility. This trust fosters a sense of ownership and accountability, often leading to more innovative solutions and improved performance.

Encouraging Calculated Risk-Taking

Creating an environment where reasonable risks are accepted and learned from is also important. Encourage calculated risk-taking and view failures as learning opportunities rather than reasons for punishment. This approach can drive innovation and help the organisation stay ahead of competitors.

Lessons from British Army Evolution: Investing in Training and Equipment

The importance of comprehensive training and proper equipment is starkly illustrated by the British Army’s experience in World War II. In the early years of the war, British forces often found themselves at a disadvantage due to inadequate training and outdated equipment. This deficiency contributed to several setbacks and defeats, particularly in the North African campaign.

British infantry training on an assault course, 1941. Photograph from the archive of the Imperial War Museum (H 12699)

However, the British military, political and industrial leadership recognised these shortcomings and acted. From 1941 onwards, there was a concerted effort to improve both training regimens and equipment quality. This included more realistic combat training (battle school), better integration of arms, and the introduction of more effective weapons and vehicles. The results of these improvements became evident in later campaigns, with British forces showing increased effectiveness and adaptability on the battlefield.

This historical example offers valuable lessons for modern businesses. Like the British Army of the early 1940s, many organisations today may find themselves ill-equipped to face rapidly changing market conditions. The solution lies in a commitment to ongoing training and investment in the right tools.

In a business context, comprehensive training should focus on developing both hard and soft skills. This includes technical training specific to job roles, as well as leadership development, decision-making workshops, and scenario-based exercises that simulate real-world challenges. By exposing employees to a wide range of potential situations, companies can build a workforce that’s adaptable and confident in their ability to handle unexpected circumstances.

Equally important is equipping employees with the right tools for the job. Just as the British Army needed modern tanks and aircraft to compete effectively, today’s businesses need cutting-edge software applications and technology. From project management tools that facilitate collaboration to data analytics platforms that enable informed decision-making, the right software can significantly enhance an employee’s ability to work autonomously and effectively.

Moreover, investing in user-friendly and efficient systems reduces friction in daily operations, allowing employees to focus on higher-level tasks rather than getting bogged down by cumbersome processes. This not only improves productivity but also boosts morale as employees feel the company is invested in their success. Without a doubt, cutting corners on equipment can produce the opposite result, causing bottlenecks in the workflow, decreased productivity, more mistakes, and unhappy employees.

The combination of comprehensive training and the right equipment pays off in increased confidence and competence across the organisation. When team members feel well-equipped, both in terms of skills and tools, they are more likely to take initiative, make informed decisions, and contribute meaningfully to the company’s success. This empowerment aligns perfectly with the principles of mission-type tactics, fostering a workforce that can adapt quickly to changing circumstances and seize opportunities as they arise.

Furthermore, this investment sends a clear message that the organisation values its employees and is committed to their growth and success. This can lead to improved job satisfaction, higher retention rates, and a more positive company culture overall.

By learning from the British Army’s evolution during World War II, modern businesses can understand the critical importance of continually updating their training methods and tools. In doing so, they can transform their workforce from one that struggles with outdated practices to one that excels in the face of new challenges.

Promoting Open Communication

Promoting open communication is essential for a decentralised approach to work effectively. Encourage the free flow of information across all levels of the organisation. This transparency helps ensure that decisions are made with the best available information and that lessons learned are quickly disseminated.

The Power of Decentralisation in Modern Business

By adopting a more decentralised approach, like the German military’s mission-type tactics, businesses can foster innovation, improve response times, and better adapt to the fast-paced, ever-changing modern business environment. This does not mean abandoning strategic oversight, but rather creating a culture where employees at all levels feel empowered to act in the best interests of the company’s mission.

Lessons from the Past, Strategies for the Future

In the words of General George S. Patton, “Never tell people how to do things. Tell them what to do and they will surprise you with their ingenuity.” By embracing this philosophy, modern businesses can unlock their full potential and outmanoeuvre their competitors in the complex battlefield of the global marketplace.

The lessons from World War II tactics remind us that in both warfare and business, adaptability and empowerment at all levels can be the key to success. As we navigate the uncertainties of the modern business world, it is time to look to the past for inspiration on how to build more resilient, agile, and successful organisations for the future.

Contact us today to discover the ways military history can inform and benefit business strategy, tactics, leadership, communication, motivation, and training.

References:

Dupuy, T. N. (1977). A Genius for War: The German Army and General Staff, 1807-1945. Prentice Hall.

Bates, Aaron (2021). The Last German Victory, Operation Market Garden 1944. Pen & Sword Military.

Van Creveld, M. (1985). Command in War. Harvard University Press.

Note: This article is for educational purposes only. The author acknowledges that while historical examples can provide valuable insights, modern business practices should always be adapted to current ethical standards and legal requirements.

The Silent Disaster: How Communication Failures Helped Doom Operation Market Garden

As we commemorate Operation Market Garden this September, it's worth reflecting on one of the most ambitious - and ultimately ill-fated - military operations of World War II. Launched in September 1944, Operation Market Garden aimed to secure a series of nine bridges in the Netherlands, potentially paving the way for a swift advance into Germany. It was a massive undertaking, involving over 34,000 airborne troops and 50,000 ground forces. Yet, what began with high hopes ended in a costly failure, partly because of a communications breakdown.

Operation Market Garden: 17 to 25 September 1944

As we commemorate Operation Market Garden this September, it's worth reflecting on one of the most ambitious - and ultimately ill-fated - military operations of World War II. Launched in September 1944, Operation Market Garden aimed to secure a series of nine bridges in the Netherlands, potentially paving the way for a swift advance into Germany. It was a massive undertaking, involving over 34,000 airborne troops and 50,000 ground forces. Yet, what began with high hopes ended in a costly failure, partly because of a communications breakdown.

At the heart of Market Garden's communication crisis was the inadequacy of the radio equipment. The British Army's standard radio set, the Wireless Set No. 22, proved insufficient for the task at hand. These radios had a maximum range of around six miles under ideal conditions, yet the Corps Headquarters was positioned a distant 15 miles away. To compound matters, the terrain around Arnhem presented additional challenges that the planners had failed to fully account for. The Arnhem area was characterised by woodland and urban buildings. These physical obstacles severely interfered with radio transmissions, further diminishing the already limited range of the No.22 sets. As a result, what should have been a vital lifeline for the paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division fighting desperately to hold the north side of the bridge at Arnhem became a silent witness to their isolation and eventual defeat.

Interestingly, a potential solution to these communication problems was literally at hand. The Netherlands boasted an extensive and sophisticated telephone network, largely intact despite years of German occupation. This network was remarkably resilient, comprising three interconnected systems: the national Ryks Telefoon system, the Gelderland Provincial Electricity Board's private network, and a clandestine network operated by Resistance technicians. Even when key exchanges were disrupted, the Dutch were still able to communicate using alternative routings.

Yet, astonishingly, Allied planners failed to fully leverage this resource. This oversight raises profound questions about the rigidity of military thinking. Why did the Allied command, known for its adaptability in other areas, fail to pivot to this seemingly obvious solution? The answer likely lies in a combination of factors: overconfidence in existing systems, security concerns, lack of familiarity with local infrastructure, the fast-paced nature of the operation, and a wariness of the Dutch Resistance.

British XXX Corps cross the road bridge at Nijmegen

The consequences of this failure were dire. While some units made limited use of the phone system, the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem - where the need was most critical - did not. They made no attempt to convey their urgent need for supplies or relief via the phone system to the corps headquarters. Ironically, Dutch agents inside the 82nd Airborne's landing area used the phone system early on D+1 to inform the 82nd that “the Germans are winning over the British at Arnhem” - the first indication that the 1st Airborne was in serious trouble.

In the face of radio failures, the Allied forces resorted to various other communication methods, each with its own limitations. Carrier pigeons proved unreliable, with many birds failing to deliver messages. Traditional forms of communication like land lines, runners, and dispatch riders were vulnerable to enemy fire and the chaos of battle. The artillery net ended up being one of the more reliable communication methods, allowing for effective artillery support and occasional relay of messages to higher command.

The communication failures during Operation Market Garden offer valuable insights into military organisational thinking. They underscore the importance of flexibility, the need to understand and potentially leverage local infrastructure, the crucial role of contingency planning, and the necessity of fostering a culture that encourages quick problem-solving and innovative thinking at all levels of command.

It's worth noting the contrast between the German military's mission-type tactics (Auftragstaktik), which emphasized flexibility and initiative, and the British Army's reliance on detailed orders and strict adherence to commands. This difference in command styles meant that German forces could often exploit opportunities more rapidly, while British forces maintained tighter control but at the cost of agility.

As we reflect on the events of eighty years ago, it's clear that the lessons learned extend far beyond the realm of military strategy. In any high-stakes endeavour, the ability to communicate effectively - and to adapt when primary methods fail - can mean the difference between success and catastrophic failure. The underutilisation of the Dutch phone system stands as a poignant example of how overlooking available resources can have far-reaching consequences.

The story of Operation Market Garden serves as a stark reminder of the critical role that effective communication plays not just in military operations, but in any complex undertaking. It's a lesson that remains relevant today, in fields ranging from business to disaster response. As we face our own challenges in an increasingly connected world, let's not forget the silent disaster that unfolded in Holland eighty years ago - and the valuable lessons it still has to teach us.

References

1. Middlebrook, M. (1994). Arnhem 1944: The Airborne Battle. Westview Press.

2. Ryan, C. (1974). A Bridge Too Far. Simon & Schuster.

3. Kershaw, R. (1990). It Never Snows in September: The German View of Market-Garden and the Battle of Arnhem, September 1944. Ian Allan Publishing.

4. Buckley, J. (2013). Monty's Men: The British Army and the Liberation of Europe. Yale University Press.

5. Beevor, A. (2018). The Battle of Arnhem: The Deadliest Airborne Operation of World War II. Viking.

6. Powell, G. (1992). The Devil's Birthday: The Bridges to Arnhem 1944. Leo Cooper.

7. Badsey, S. (1993). Arnhem 1944: Operation Market Garden. Osprey Publishing.

8. Hastings, M. (2004). Armageddon: The Battle for Germany, 1944-1945. Alfred A. Knopf.

9. Zaloga, S. J. (2014). Operation Market-Garden 1944 (1): The American Airborne Missions. Osprey Publishing.

10. Clark, L. (2008). Arnhem: Operation Market Garden, September 1944. Sutton Publishing.

11. MacDonald, C. B. (1963). The Siegfried Line Campaign. Center of Military History, United States Army.

12. Bennett, D. (2007). Airborne Communications in Market Garden, September 1944. Canadian Military History, 16(1), 41-42.

13. Greenacre, J. W. (2004). Assessing the Reasons for Failure: 1st British Airborne Division Signal Communications during Operation 'Market Garden'. Defence Studies, 4(3), 283-308. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1470243042000344777#d1e290

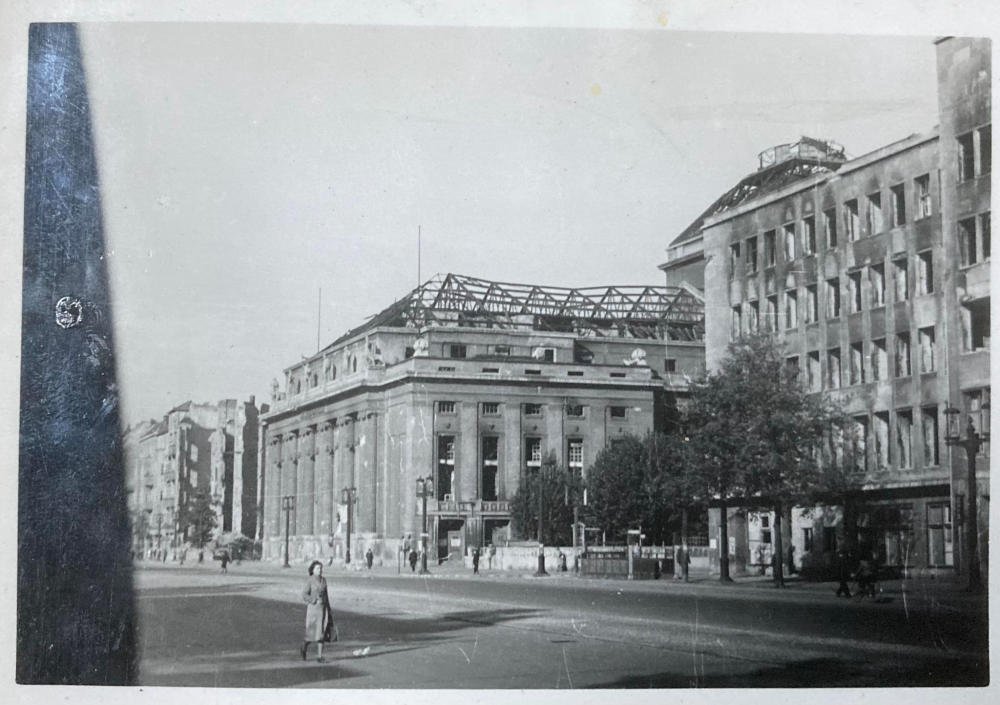

Explore Berlin's Second World War History

In this guest article, Matti Geyer of www.toursofberlin.com provides a guide to some of Berlin's most significant Second World War sites, each offering a poignant glimpse into this crucial chapter of the city's history.

If you're fascinated by Second World War and Holocaust history, Berlin is a must-visit destination. The city is home to many solemn yet impactful reminders of the war's horrors. Visitors can explore the ruins and bullet-scarred structures that vividly recount tales of destruction and resilience. You can discover bunkers that echo wartime preparations, and visit Holocaust memorials that, though sombre, reflect Germany's commitment to confronting its past. Dive into remarkable museums that strive to educate, ensuring that the lessons of history are not forgotten. In this guest article, Matti Geyer of www.toursofberlin.com provides a guide to some of Berlin's most significant Second World War sites, each offering a poignant glimpse into this crucial chapter of the city's history.

1. Bunkers:

Boros Bunker: Constructed as an air-raid shelter during World War Two, the Boros Bunker in Mitte has evolved into a contemporary art gallery. Originally built to protect Berliners from aerial bombardment, this massive structure later witnessed various uses, from a tropical fruit warehouse to a techno club, before becoming a testament to the city's creative spirit.

Anhalter Bunker: Once a colossal air-raid shelter connected to the Anhalter Bahnhof, this bunker stands as a formidable reminder of Berlin's wartime preparedness. Now a museum, it provides a chilling insight into the harrowing experiences of those seeking refuge during air raids, complete with preserved gas masks and eerie remnants of the past.

RAW Kegelbunker: Nestled in the heart of Friedrichshain, the RAW Kegelbunker has a unique round shape, and was to protect workers from a nearby train depot. It now serves as a climbing wall.

Führerbunker: The Führerbunker, where Adolf Hitler spent his last days before his suicide, holds a solemn place in history. It was situated beneath the garden of the Reich Chancellery. The bunker site, now a parking lot where local residents walk their dogs, was destroyed in the 1980s.

2. WW2 Ruins:

Kaiser-Wilhelm-Memorial Church: The haunting silhouette of the Kaiser-Wilhelm-Memorial Church's damaged spire serves as a poignant symbol of wartime destruction. Bombed during an air raid in 1943, the church was preserved as a memorial, with its adjacent modernist structure providing a striking contrast to the ruins.

Anhalter Bahnhof: Once one of Berlin's biggest railway stations, the Anhalter Bahnhof fell victim to several bombing campaigns. Its skeletal remains stand as silent witnesses to the devastating impact of air raids, a ghostly reminder of the city's former transportation hub. There is a plan to build an "exiles museum" next to the site, dedicated to all those who had to emigrate from Nazi Germany.

Jewish Cemetery Schönhauser Allee: The Jewish Cemetery Schönhauser Allee, which still bears visible war damage, bomb craters, and damaged graves, reflects the tragic toll of World War II as well as the Holocaust. Inscriptions, decorations, and metal grave fences were stolen and melted down. Towards the end of the war, foxholes were dug on the cemetery grounds and fortified with tombstones. Other stones were removed from the graves and randomly piled on top of each other. The cemetery, consecrated in 1827, was the only burial site of the Berlin Jews for more than 50 years. It is located in the triangle between Schönhauser Allee, Kollwitz- and Knaackstraße. There are still remains of cisterns on the site. In one of them, young deserters hid in the last days of the war in 1945. However, they were discovered by the Gestapo and hung on the cemetery trees.

3. Bullet Holes:

Museum Island: The Neues Museum on Museum Island proudly preserves bullet holes as scars of conflict, offering a visceral connection to the city's wartime struggles. These visible reminders evoke a sense of the fierce battles that unfolded in the heart of Berlin.

Martin Gropius Bau: This historic exhibition hall bears the scars of war, with bullet holes marring its grand façade. The building stood right next to the Gestapo HQ, which no longer exists.

S-Bahn Viaduct between Friedrichstraße and Museum Island: During the intense battles of 1945, the S-Bahn viaduct served as a crucial defensive barrier. The Soviet 7th Corps encountered significant resistance here, resulting in the viaduct's enduring scars that visitors can still see today.

4. Holocaust Memorials:

Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe: The solemn expanse of the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe stands as a stark reminder of the Holocaust. Designed by Peter Eisenman, this field of 2711 concrete slabs provides a contemplative space for remembrance and reflection.

Memorial to Murdered Sinti & Roma: Adjacent to the Brandenburg Gate, this memorial commemorates the persecution and genocide of up to 500,000 Sinti and Roma people during the Nazi era. The tranquil setting invites visitors to ponder the impact of intolerance on marginalised communities.

T4 Memorial: Honouring the victims of the Nazi euthanasia program, the T4 Memorial in Tiergarten serves as a poignant reminder of the atrocities committed during this dark chapter of history. The Nazis targeted people with severe mental and physical disabilities, and those who seemed to have disabilities, because they believed that disabled people were a burden to society and the state. From 1939 to 1941, they ran a 'euthanasia' programme, called the T4 programme. The programme got its name from Tiergartenstrasse 4, the address where they coordinated it.

Grunewald Platform 17 Memorial: The Grunewald Station Platform 17 bears witness to the tragic deportations of Berlin's Jewish community. The memorial, adorned with inscriptions for every train that left from here to the camps and ghettos cross Eastern Europe, serves as a poignant reminder of the lives disrupted and lost during the Holocaust.

5. Nazi Architecture:

Olympic Stadium: Constructed for the 1936 Summer Olympics, the Olympic Stadium symbolises Nazi grandiosity. Today, it stands as a testament to the manipulation of architecture for propagandist purposes, though it is still used for sporting events.

Air Force Ministry: The remnants of the Air Force Ministry, once a colossal symbol of Nazi power, reflect the megalomaniacal architectural ambitions of the Third Reich. Once one of the biggest office buildings in Europe, it miraculously survived the Second World War and now houses the German finance ministry.

Tempelhof Airport Building: The colossal Tempelhof Airport building, with its imposing Nazi-era architecture, remains an iconic landmark. Originally designed as an emblem of Hitler's vision for German aviation, the airport now serves as a multifaceted public space. Upon completion, it was the largest building in the world, until the Pentagon overtook it.

6. Museums:

Topography of Terror Documentation Centre: Built on the former site of the SS and Gestapo headquarters, the Topography of Terror Documentation Centre provides a chilling insight into the mechanisms of Nazi repression. The outdoor exhibition, complemented by preserved ruins, immerses visitors in the historical context.

Otto Weidt Workshop for the Blind: Otto Weidt's workshop, tucked away next to the Hackesche Höfe, served as a sanctuary for blind and deaf Jews during the Nazi regime. The workshop's survival stands as a testament to one man's defiance against persecution. A small windowless room that was hidden behind a shelf and housed an entire family for several months is especially impressive.

Resistance Museum in Bendlerblock: Nestled within the historic Bendlerblock, the Resistance Museum offers a detailed narrative of anti-Nazi resistance efforts, emphasising the courage and sacrifice displayed by individuals such as Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg and members of the Reserve Army that used to be headquartered here. The exhibition halls vividly depict stories of those who sought justice during this tumultuous period, providing a compelling insight into the resilience of the resistance movements. It also marks the place where Stauffenberg was shot.

7. Additional Recommendations:

Soviet Memorial Treptower Park: The Soviet Memorial in Treptower Park is a grand tribute to the Red Army soldiers who lost their lives in the Battle of Berlin. The monumental statue of a Soviet soldier holding a German child and smashing a swastika with a sword stands at the centre. Opposite the statue stand two marble triangles. The marble used in their construction originally came from the Reich Chancellery building.

Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp: located north of Berlin, the camp serves as a chilling reminder of the Holocaust's horrors. Established in 1936, Sachsenhausen initially served as a model camp, evolving into a centre for SS training. The preserved barracks, watchtowers, and historical exhibits depict the systematic oppression and dehumanisation faced by inmates. The stark barracks reveal harsh living conditions, while looming watchtowers symbolise constant surveillance. Visiting Sachsenhausen is an emotional journey that ensures the preservation of memory and honours the countless lives lost during this dark period in history.

In conclusion, these immersive explorations into Berlin's World War II remnants offer a profound understanding of the city's resilience and collective memory. To delve even deeper into this historical tapestry, consider joining a guided tour specialising in the Third Reich, World War II, and Holocaust history. Knowledgeable guides provide contextual insights, transforming each location into a living testament to the city's enduring spirit amidst the shadows of its wartime past.

To learn more about Tours of Berlin or to make a reservation visit the website now: https://www.toursofberlin.com/private-tours/third-reich-ww2-berlin-tour

How AI Can Help You Discover and Celebrate Your Military Ancestors

In this blog post, we will explore how AI can help you discover more about your military ancestors in two ways. First, AI can assist you in conducting historical research. Second, AI can now help to transform old black-and-white family photos into moving colour video footage, enabling your ancestors to tell their own stories.

If you are interested in your family history (genealogy), you may have wondered if any of your ancestors served in the military. Military service is a common and significant part of many people’s heritage, and learning more about it can enrich your understanding of your family’s past. However, finding and accessing military records can be challenging, especially if you don’t know where to look or how to interpret them. Moreover, even if you manage to find some information about your ancestor’s military service, you might still feel a gap between you and them, as you only have some names, dates, and facts, but no sense of who they were as individuals, what they looked like, what they sounded like, and how they lived. This is where AI can help.

AI, or artificial intelligence, is the ability of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, and problem-solving. AI has been advancing rapidly in recent years, thanks to the availability of large amounts of data and powerful computing resources. AI has many applications in various fields, including military history research and presentation.

In this blog post, we will explore how AI can help you discover more about your military ancestors in two ways. First, AI can assist you in conducting historical research. Second, AI can now help to transform old black-and-white family photos into moving colour video footage, enabling your ancestors to tell their own stories.

How AI Can Help You Conduct Historical Research

One of the main challenges of military history research is finding and accessing relevant sources. Military records are often scattered across different archives, libraries, museums, and online databases, some of which may be inaccessible or incomplete. Moreover, military records can be difficult to read and understand, as they may use unfamiliar terminology, abbreviations, symbols, or handwriting. Furthermore, military records may not provide enough information about your ancestors’ personal lives, such as their motivations, emotions, opinions, or relationships. AI can help you overcome some of these challenges by providing you with tools that can search, analyse, and synthesize large amounts of data from various sources.

For example, AI can help you:

Find and access military records that match your criteria, such as name, date of birth, place of origin, rank, unit, service number, etc.

Extract and organise relevant information from military records, such as dates, locations, events, awards, casualties, etc.

Translate and explain military terminology, abbreviations, symbols, or handwriting that may be unfamiliar or unclear to you.

Cross-reference and verify information from different sources to ensure accuracy and completeness.

Fill in the gaps or resolve the contradictions in the available information by using historical context and logic.

Generate summaries and reports of your findings that highlight the key points and provide additional details.

By using AI tools for historical research, you can save time and effort that you would otherwise spend on searching for sources manually. You can also gain a deeper and broader understanding of your ancestors’ military service by accessing more information from more sources. You can also learn more about the historical background and significance of your ancestors’ service by getting explanations and interpretations from experts. However, many archives have yet to fully digitise their collections. As a result, having to do some manual research is almost inevitable when conducting military history research.

How AI Can Help You Celebrate Your Military Ancestors

Military history research can be a fascinating journey, but it’s not always easy to share your findings in a way that is engaging and meaningful. Military records may provide some facts about your ancestors’ service, but they may not capture their personality or character. Old family photographs may give you a glimpse of what your ancestors looked like but do not convey their voice or tone. Wouldn’t it be amazing if you could see your ancestors in colour and hear them speak for themselves?

Visit our Virtual Ancestor webpage now to learn more.

Virtual Ancestor

At The War Years, we offer a new service called the Virtual Ancestor. Using the latest AI tools, we can transform a few old fading photographs into vibrant colour videos of your ancestors. Your ancestors will be able to tell their own story in the first person, based on our research of their military service. You will be able to see and hear your ancestor and learn more about their military service, their achievements, their challenges, and their personalities.

With Virtual Ancestor, you can celebrate your military ancestors in a unique and engaging way. It’s a great way to connect with your family history and learn more about your ancestors’ lives.

Contact us today, to learn more about our Virtual Ancestor and similar AI-generated historical content.

Dick Hewitt and the Desert Air Force

Dick Hewitt served as an Armourer with a mobile fighter squadron as part of the Desert Air Force (DAF) from 1943 to 1945. During Dick’s time in the RAF, he kept a diary, although this was against regulations. Although the diaries are incomplete, they have provided enough clues and information to be able to retell the wartime story of one Leading Aircraftman and his role in the Allied campaign for Italy.

Dick Hewitt served as an Armourer with a mobile fighter squadron as part of the Desert Air Force (DAF) from 1943 to 1945. During Dick’s time in the RAF, he kept a diary, although this was against regulations. Although the diaries are incomplete, they have provided enough clues and information to be able to retell the wartime story of one Leading Aircraftman and his role in the Allied campaign for Italy.

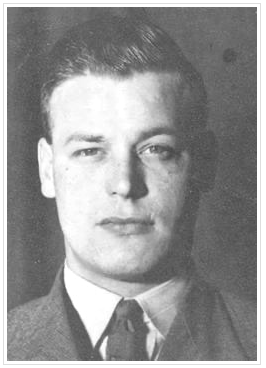

Dick Hewitt was born on Thursday 18 April 1901 in Leicester. Dick passed away on Friday 7 June 1985, aged 84, in Birmingham.

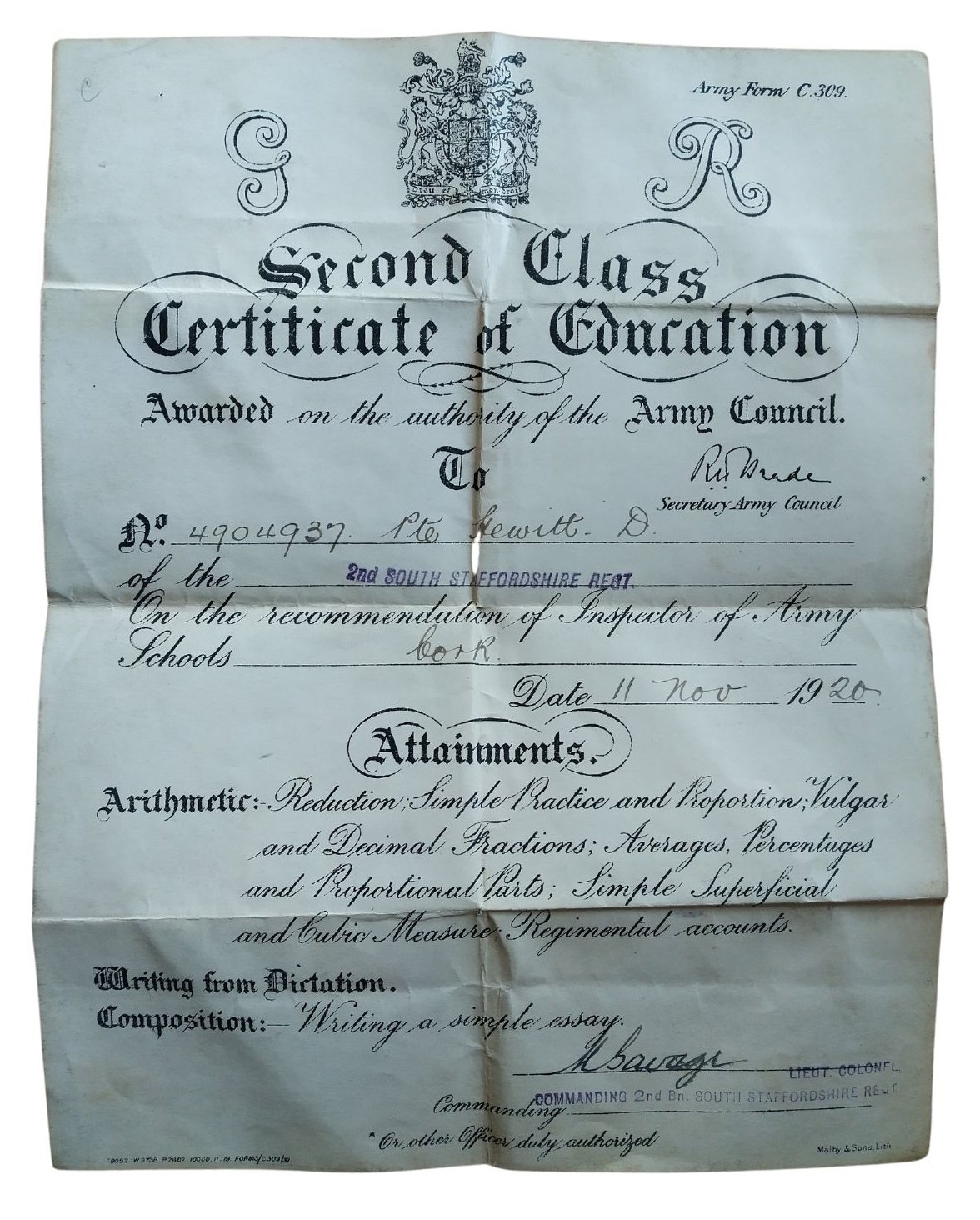

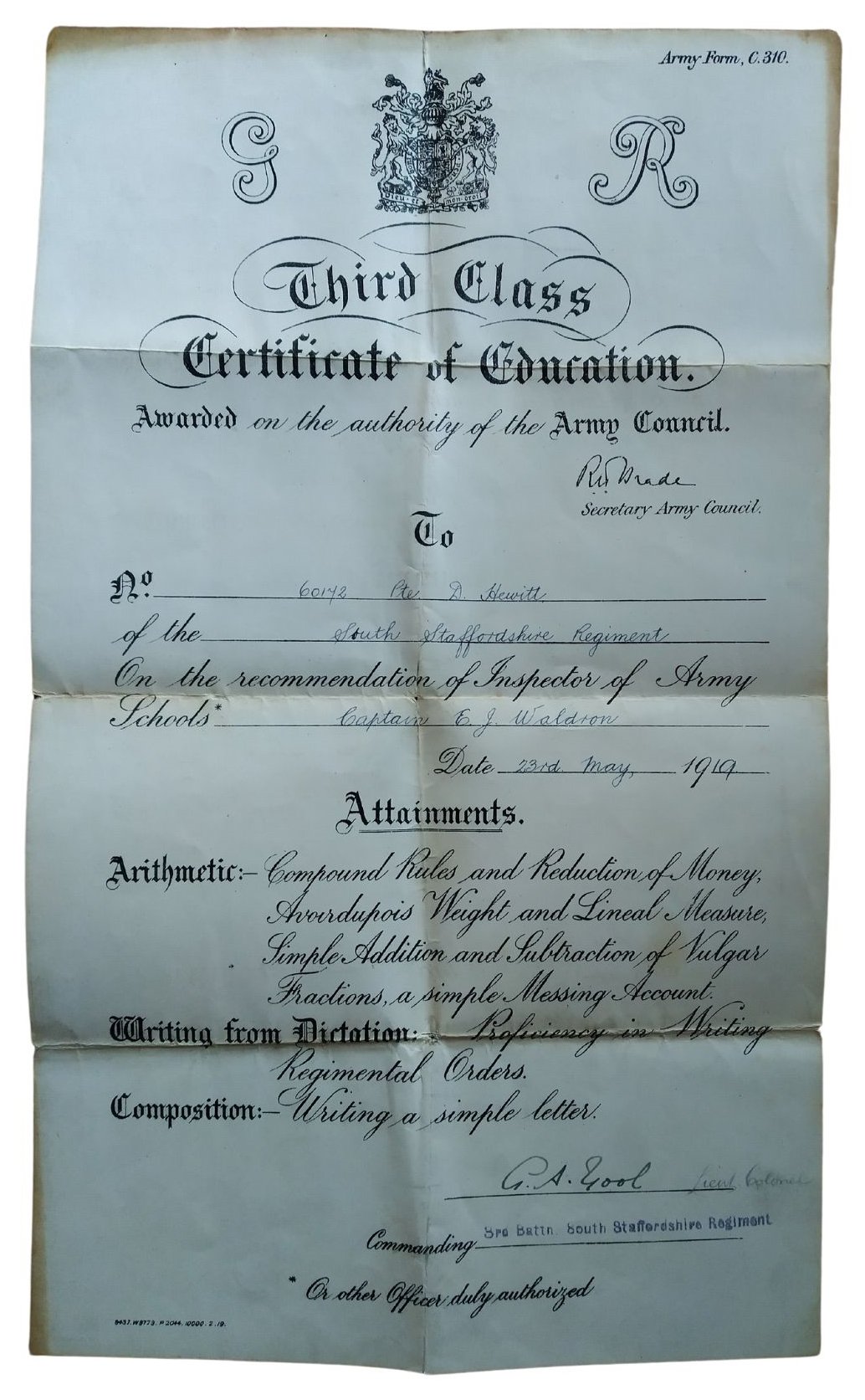

Service in the British Army

Amongst Dick’s personal papers, I found several Certificates of Education awarded to Private D. Hewitt, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment issued in May 1919 and November 1920, which suggests that Dick was conscripted into the Army (as conscription did not end until mid-1919). The 2nd Battalion spent the immediate post-war years in Ireland during the War of Independence (1919-21). One of Dick’s Certificates of Education was issued from Cork, which confirms that he was stationed in Ireland. The Corps of Army Schoolmasters was replaced in 1920 by the Army Educational Corps (AEC). A brief search of The National Archives and British Army World War I Service Records, 1914-1920, found no record of Dick’s early military service with the South Staffordshire Regiment.

Dick was in his early to mid-forties during the Second World War. Most of his comrades would have been in their late teens to mid-twenties. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as an older man, it appears Dick’s comrades referred to him as ‘Pops’ based on some post-war correspondence found amongst Dick’s personal papers. Dick was married with two children while serving in the RAF and he sent money home to his family whenever he was able.

Service in the Royal Air Force

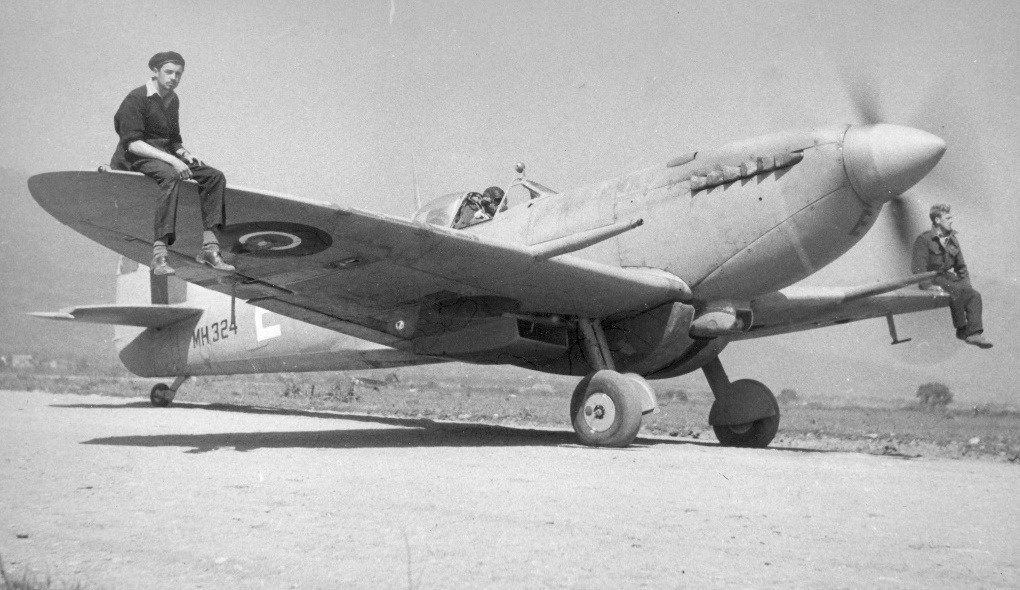

Dick’s RAF Service No: 1468728. He held the rank of Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and qualified as an Armourer. Dick served with 324 Wing, No. 93 Squadron, Royal Air Force, part of the BNAF (British North Africa Force). As part of a highly mobile fighter squadron originally equipped with Spitfire Mk. Vs and later Mk. IXs, Dick served in North Africa, Malta, Italy, Corsica, and southern France.

The Role of the Armourer

As an Armourer with No. 93 Squadron, Dick’s role was to arm the Spitfires of No. 93 Squadron with ammunition and bombs, regularly strip and clean the guns and perform general maintenance. Based on Dick’s diary entries, he also worked on fitting supplementary fuel tanks to the Spitfires, which extended their range.

Diary Entries: UK Training & Posting Overseas 1942

9 January: Left Halton Camp for Kirkham. RAF Halton, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire, was a major RAF training centre. Similarly, RAF Kirkham, Lancashire, was the main armament training centre for the RAF from November 1941.

1942: Passed Armourer’s course, A.C. II. – Aircraftman 2nd class.

30 March 1942: Passed L.A.C. exam – Leading Aircraftsman.

1942: Arrived at RAF Speke. Note: Today, RAF Speke is Liverpool John Lennon Airport.

1942: Promoted A.C. I. - Aircraftman 1st class.

11 November: Left Wareford for overseas. By train to Scotland. Arrived at Greenock at 08.00hrs.

13 November: Boarded the HMT (His Majesty's Transport) Bergensfjord (a former Norwegian ocean liner). Navy, Army, and Air Force personnel were all on board.

14 November: Left Greenock at 05.00hrs heading for the North Atlantic. There are 16 boats in our convoy escorted by Royal Navy Destroyers.

20 November: Nearing the Mediterranean, passed Gib (Gibraltar) at midnight. Could see Tangiers lit up at night.

Tunisia 1942

8 December: Arrived at Souk-El-Arba station (Tunisia) at 08.00hrs. We’re about 40 miles behind the frontline.

19 December: Had a terrible sight to witness as one of the (ditto) ground crews was taken up in the air sitting on the tail of a plane. The kite (RAF slang for aircraft) crashed on landing throwing the man right over the front of the kite. He sustained serious injuries to his legs. Note: During bad or windy weather, it was common practice to have a member of the groundcrew sit on the tailplane of an aircraft as it taxied to its take-off position. Usually, the groundcrew would dismount while the pilot carried out their pre-flight checks.

30 December: Nearly killed when strafed by a Jerry aircraft. Had to dive for cover on the roadside. Learned all the Squadron’s tools were lost when the boat carrying them was torpedoed on 18 December.

The Desert Air Force (DAF) in Tunisia

The Allied campaign in Tunisia started in November 1942. By late March and throughout April 1943, the Desert Air Force (DAF) was conducting bombing and strafing missions (interdiction) on infrastructure, such as bridges, supply routes, Luftwaffe airbases, Tunisian ports, and the capital of Tunis. They also flew missions over Sicily and southern Italy. The aim of the missions was twofold. First, starve Axis forces of everything from fuel and ammunition to food, and thus weaken their ability to resist. The second was to establish Allied air superiority over the battle space and enable the ground forces to make a final push on the Tunisian capital. The DAF also provided close air support to Allied ground forces.

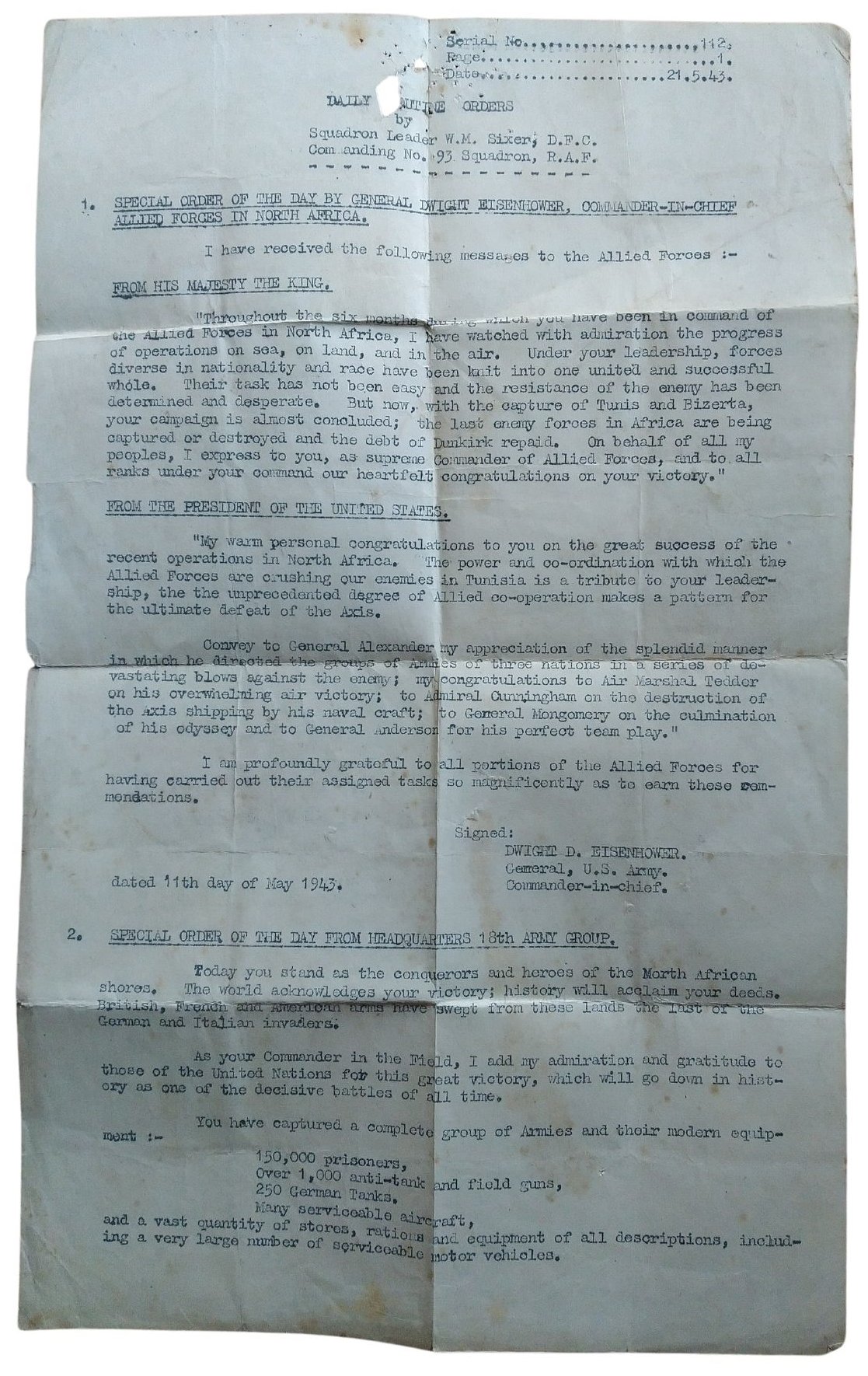

On 7 May 1943, Allied armour rolled into Tunis, taking many Axis troops based in the city completely by surprise. By 10 May, the Luftwaffe had evacuated what aircraft and equipment they could salvage. The capture of Tunis led to an Axis surrender and the capture of around 250,000 prisoners. It was a significant Allied victory.

No 72 Squadron, 324 Wing RAF. Spitfire, North Africa 1943.

Diary Entries: Tunisia 1943

3 February 1943: Jerry bombed drome (aerodrome) in the morning. Three RAF were killed and five wounded. Bombs were released from FWs (Focke Wulf 190 fighter-bombers) while I was having a wash. Eight Spits U.S. (unserviceable).

22 February 1943: Fortresses (B.17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber) dropped bombs on Souk-El-Arba, 25 people killed by mistake. Note: There were two airfields at Souk-El-Arba both located near what was at the time the village of Souk-El-Arba but since 1966 has been known as Jendouba. The site is about 81 miles west-southwest of Tunis.

1 March 1943: Kites on a bomber escort, one Spit and one ME (presumably a Messerschmitt Bf 109) shot down during a dogfight over the drome at 12.30hrs.

2 March 1943: Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham arrived at the drome. Note: Today, Coningham is chiefly remembered as the person most responsible for the development of forward air control parties directing close air support, which he developed as commander of the Western Desert Air Force between 1941 and 1943.

16 March 1943: Dive-bombed without warning. Dived under a kite and watched bombs bursting. AA (anti-aircraft artillery) returned fire. One soldier was killed.

April 1943: Squadron mainly assigned to bomber escort missions. Note: The Allies heavily bombed Axis (Luftwaffe and Italian) airfields and infrastructure such as bridges. Enemy air activity diminished as the Allies' bombing campaign intensified.

7 May: Tunis reported taken.

10 May: Bizerta reported taken. After being reported missing Red Herbert got back to the airfield with 20 released prisoners.

12 May: Thousands of prisoners taken. End of the campaign in Africa.

14 May: Move to a new drome between Tunis and Bizerta. Met thousands of prisoners and passed through the battlefront. Saw plenty of wrecked tanks, etc.

15 May: On new drome. Found a camp bed, very useful. Bags of rifles, etc. Crashed and wrecked Ju-52s all over the airfield and two ME-109s. Had to be careful of boobytraps and mines. Note: The Junkers Ju-52 is a three-engine transport aircraft and was a mainstay of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe).

20 May: Victory Parade at Tunis. Thousands of troops were in the town.

24 May: Went souvenir hunting. Found the famous Ace of Spades Squadron drome. Every kite was either burned out or shot up. Bags of stores lying about. In this diary entry, Dick is referring to the Jagdgeschwader 53 (JG 53) fighter-wing of the Luftwaffe, known as the "Pik As" (Ace of Spades).

26 May: Move to a drome at Mateur, which is situated between Bizerta and Tunis.

8 June: Drove to Sfax harbour (south of Tunis) and boarded a Landing Ship, Tank (LST).

9 June: Arrived in Malta.

Dick Hewitt, on the left, sitting on the wing of a Spitfire. Date and location of photograph unknown.

Malta 1943

20 June: The King arrived in Malta. He visited the drome.

24 June: Sir Archibald Sinclair (Secretary of State for Air) visited the drome in the afternoon and gave a speech. He thanked us for our work in North Africa.

10 July: Operation HUSKY. Sicily was invaded by troops at 02.30hrs. Kites on dawn sweeps (sorties) over Sicily. Worked until 23.00hrs.

Operation HUSKY, Allied Invasion of Sicily, 9 July - 17 August 1943

Prior to an Allied invasion of the Italian mainland, it was necessary to capture the island of Sicily. Axis forces based on Sicily were resupplied across the Messina Strait. The key target of the invasion was the port of Messina, the link to the Italian mainland. But it was heavily defended and its distance from North Africa meant the Allies could not attack it directly.

A major concern and threat to the invasion fleet was the Italian island of Pantelleria, about 50 miles from the Tunisian coast and halfway to Sicily. The island could be used by Axis forces to attack the invasion fleet at sea. Consequently, the island was heavily bombed and then shelled by the navy. Finally, on 11 June 1943, British troops landed at the main harbour, and the island garrison surrendered.

During June and July 1943, the Desert Air Force started to relocate to Malta in preparation for the invasion of Sicily.

On 9 July, British, Commonwealth and American troops started landing on Sicily preceded by airborne forces. In the weeks prior to the invasion, the Allies had launched a concerted aerial bombardment of the Axis air forces on Sicily – winning air superiority. However, bad weather on the night of 9 July resulted in the airborne forces being scattered. Once ashore, the British 8th Army initially made steady progress north until checked at Catania. The Americans, under General Patton, took Palermo. After fighting a defensive campaign for about two weeks, the Axis forces started to withdraw. After 38 days, Allied forces finally took Messina. However, around 120,000 enemy troops had been successfully evacuated. At the time, Operation HUSKY was the largest amphibious invasion of the Second World War with over 180,000 men, 4,000 aircraft, and 3,000 vessels deployed.1

Italy 1943

19 – 20 July: Moved by tank landing craft to Sicily. Arrived Pachino beach (southern tip of Sicily) at 06.00hrs.

12 August: Jerry bombed Lentini Drome (south of Catania) during the night (surprise raid) 24 kites were written off, and 96 airmen were killed or wounded (322 Wing).

13 August: Jerry retreats toward Messina evacuating troops.

17 August: Messina reported taken.

18 August: End of Sicilian Campaign.

27 August: Moved to Gerbibi near Mount Etna (west of Catania).

7 September: Arrived Falcone (north coast of Sicily).

Operation AVALANCHE – Allied landings at Salerno, 8/9 September 1943

German forces correctly anticipated the Allied landings near the port of Salerno by the U.S. 5th Army and concentrated five divisions against the beachhead. Initially, it appeared the Allies might be thrown back into the sea. However, Allied airpower gradually strangled the Germans' ability to resupply its land forces, and gradually they had to give ground. However, the Germans exploited the mountainous terrain to their full advantage as they staged a fighting withdrawal northward. Eventually, Allied progress was brought to a halt along the heavily fortified ‘Gustav Line’.

8 September: We were told landings would be made near Naples during the night (Operation AVALANCHE). Ready to move to Naples. Italy surrendered and Naples invaded in the early hours.

During the next few days, the Squadron flew numerous sorties over the beachhead providing air support to the ground forces.

23 September: Moved to Milazzio (west of Messina) and boarded transport, moved off at 20.30hrs headed for the Italian mainland.

24 September: Convoy shelled. Landed midday near Salerno.

28 September: Moved to Battipaglia drome (east of Salerno).

11 October: Moved to Naples passing through Pompei.

30 October: Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park landed at Drome. Note: Park played a pivotal role in winning the Battle of Britain.

Usually, a Spitfire Squadron had twelve aircraft split into two flights of six (A and B Flights). In combat, the aircraft would typically divide into smaller groups of two or three aircraft.

12 November: German fighter bombers attacked a nearby airfield. The Squadron’s aircraft were scrambled and pursued the enemy aircraft, but they escaped.

14 November: 324 Wing broke the record for the number of kites shot down in 12 months: 301.5.

22 November: Enemy aircraft strafed the main road to Rome. Six enemy aircraft were shot down and another six were probably downed.

24 November: Six aircraft on shipping patrol and ‘L’ on patrol of the front line (presume that the letter ‘L’ refers to an individual aircraft).

26 November: A German Ju-88 (The Junkers Ju-88 twin-engine multirole combat aircraft) was shot down by 435 Squadron. Kites on mine sweeping patrol. Enemy aircraft over our drome and heavy AA fire (anti-aircraft artillery sometimes referred to by the British and Commonwealth forces as Ack-Ack).

28 November: Strafed road transport – four trucks and two staff cars hit. F/O (Flying Officer - a junior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force) Swain dived too low, hit some trees, and then went straight into the ground.

2 December: Kites on bomb line patrol. Note: The bomb line is a line or limit beyond which aircraft may make attacks on the enemy without risking damage to their own troops.

5 December: Kit bags lost at BARI (Bari is a port city on the Adriatic Sea and the capital of southern Italy’s Puglia region). 12 ships sunk in the harbour. Souvenirs, etc. all lost, and 500 Woodbines (British brand of cigarettes).

7 December: Red Herbert shot down a Me-109, his first kill. Note: The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was the backbone of the Luftwaffe’s fighter force along with the Focke-Wulf Fw-190. Me-109 and Bf-109 are used interchangeably to refer to the aircraft.

10 December: Jet tanks fitted. Note: I am assuming this diary entry refers to the ground crew fitting jettisonable extra fuel tanks to the Spitfires. These fuel tanks extended the range a Spitfire could fly but also somewhat limited the aircraft’s performance. The fuel tanks were fitted under the central section of the fuselage and carried a 30, 45 or 90-gallon capacity. They were also known as drop tanks or ‘slipper’ tanks and could be jettisoned after use or before engaging enemy aircraft.

16 December: FLT (Flight Lieutenant) Taylor was shot down and belly-landed on a beach. Returned safely the next day.

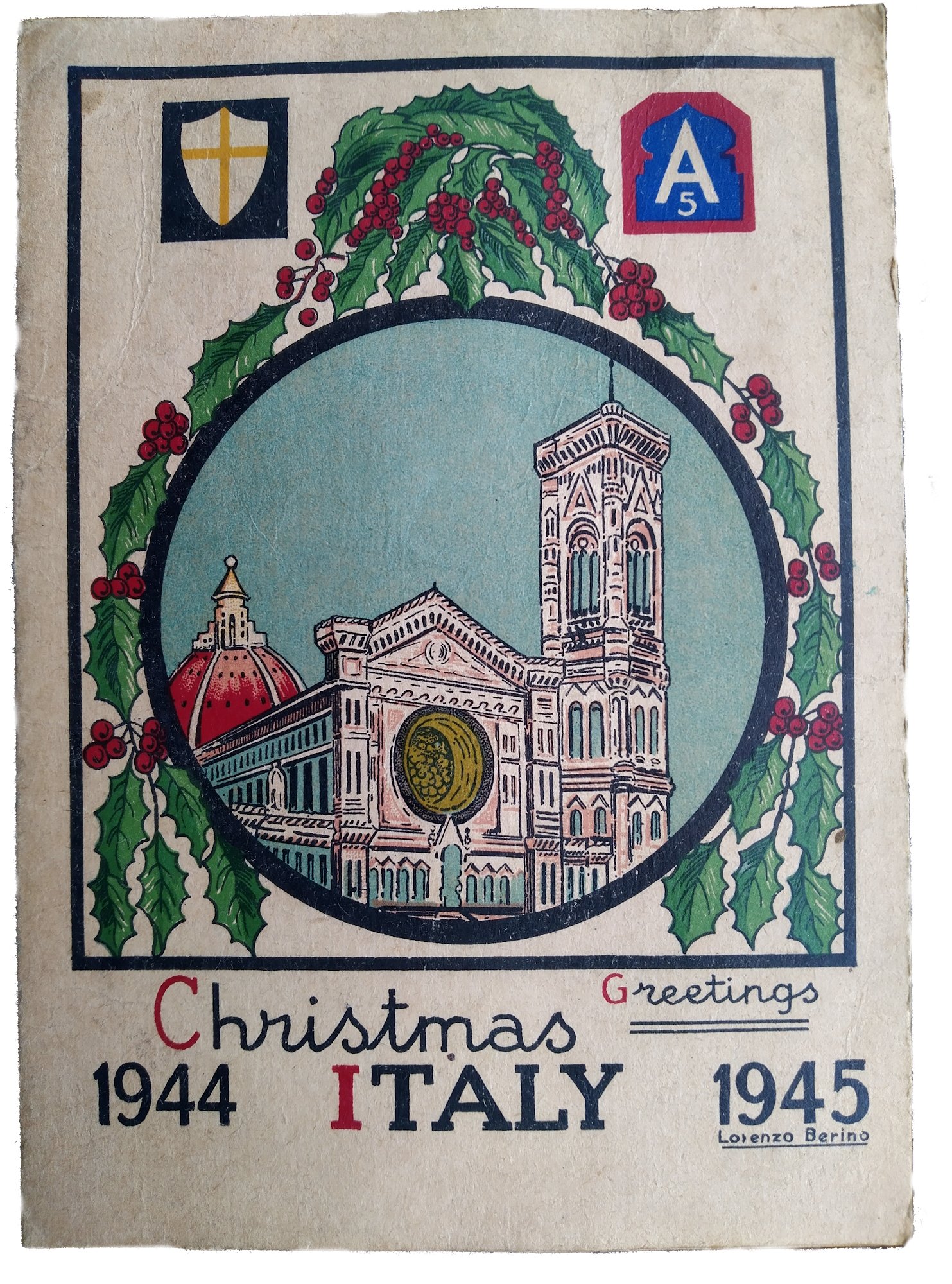

Christmas: Dick seems to have enjoyed the Christmas period with plenty to eat and drink. He complained of feeling hungover on Christmas day after too much merry-making the night before.

The weather during the late autumn and early winter of 1943/44 steadily deteriorated. The Squadron was often at half-hour readiness (held ready to scramble into action if required). When not working, Dick appears to have spent much of his free time visiting local towns, going to the cinema and the occasional concert, and following the inter-squadron football matches. He was also assigned to sentry duty.

Italy 1944

11 January: Typhus is very bad in Naples.

13 January: Bombers over all day (Flying Fortresses) about 950 passed overhead on their way to bomb Cassino (Between 17 January and 18 May, Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line defences were attacked on four occasions by Allied troops.). All fives went away replaced by nines. Note: Dick is referring to the replacement of Mk. V Spitfires with the new Mk. IX variant.

14-16 January: Prepared to move to a new location. Left Naples at 10.30hrs and arrived at the new drome about 14.00hrs. Crossed the Volturno River Bridge.

18 January: Watched Bostons drop their loads on enemy positions and return safely. In this diary entry, Dick is referring to the American-built Douglas A-20 Havoc medium bomber that was renamed the Boston by the RAF.

19 January: 15 miles behind front lines – guns firing.

Operation SHINGLE, the Battle of Anzio, 22 January – 5 June 1944

To break the deadlock and get the Allied advance moving again, the High Command decided to launch another amphibious landing. The intention of Operation SHINGLE was to bypass the Gustav Line, forcing the Germans to pull troops back from Cassino and open the road to Rome. Operation SHINGLE was launched on 22 January 1944. Initially, the landings were unopposed. However, the Allies quickly lost the initiative and failed to break out from the beachhead. Instead, by 25 January, the Germans counterattacked with elements of five divisions and quickly surrounded the Allied landing force. For months, the Anzio campaign dragged on with neither side able to gain a significant advantage. Eventually, the deadlock was broken when the Allies launched a series of new operations compelling the Germans to redeploy their limited forces. On 4/5 June, Rome fell, but the Germans remained undefeated and pulled back to a new defensive position known as the Gothic Line.2

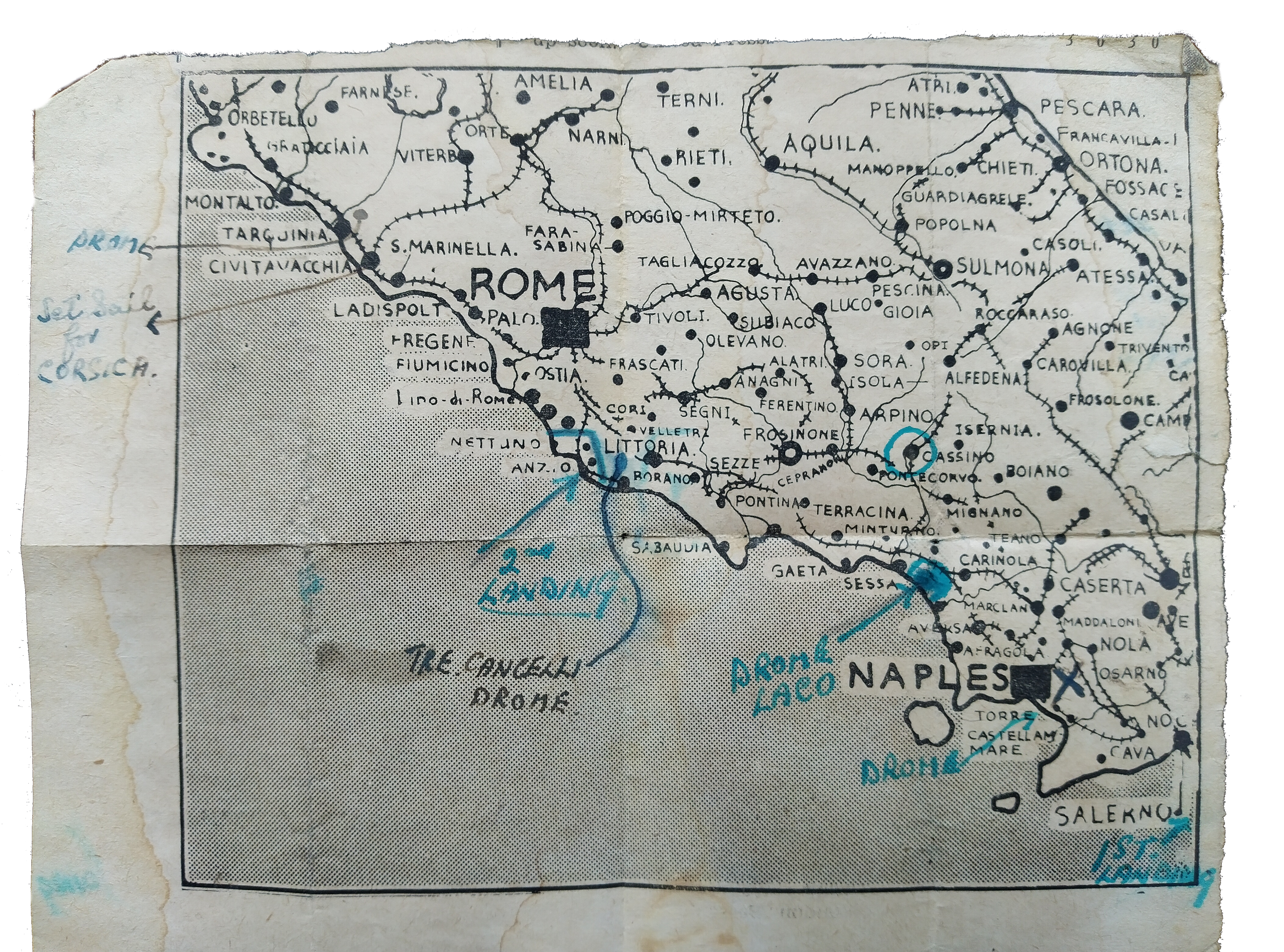

21 January: Told that another landing would be made 50 miles north of here during the night at Cape ANZIO.

22 January: Landings successful – no opposition. Went to the village of Mondragone (situated on the coast about 28 miles northwest of Naples). The village had been badly bombed.

27 January: The Squadron fetched four down and two damaged for the loss of one pilot missing. Dick often uses the term ‘fetched down’ in his diaries to indicate that the Squadron had either shot down or damaged enemy aircraft.

28 January: The Squadron is down to six serviceable aircraft due to prangs. Plenty of shelling night and day. Note: The loss of aircraft due to non-operational accidents seemed common at the time. Between 1939 and 1945 RAF Bomber Command, for example, lost 1,380 aircraft within the UK on operational flights and 3,986 aircraft in non-operational accidents.

7 February: Two MEs (Messerschmitt Bf 109s) shot down. Red Herbert forced landing with serious injuries.

10 February: Cruisers shelling enemy positions night and day.

12 February: Jerry active over ANZIO beach, bombing and strafing.

15 February: Red Herbert died in hospital. Note: In fact, Flight Sergeant Henry Ivor (Red) Herbert, Service Number: 415189, 93 Sqdn., Royal New Zealand Air Force, died on 7 February 1944, age 20. Red is buried at the Anzio War Cemetery. He had been flying Spitfire Mk. IX MA509.

16-17 February: Dick says the Wing shot down seven enemy aircraft over the ANZIO beachhead. He also writes that ‘R’ and ‘Z’ both had forced landings at ANZIO. I am assuming that Dick is referring to individual aircraft using the RAF letter code. The RAF used three-letter codes to identify aircraft from a distance. Two letters before the roundel, for the squadron to which the aircraft belonged, and another letter after the roundel for the individual aircraft.

1 March: Record of enemy kites destroyed 343.5.

16 March: Cassino was heavily bombed for two days.

18 March: Went on a day trip to Napoli (Naples). Returning at night saw Mount Vesuvius in eruption. Most wonderful sight to see. Hot lava running down the sides. Still visible at 30 miles. The volcanic eruption had started the day before and lasted for about ten days.

22 March: Mount Vesuvius – People have started to evacuate southern Naples.

23 March: Finished work at 17.00hrs and went on a trip to see Mount Vesuvius at night. A sight worth seeing.

24 March: W/O (Warrant Officer) Bunting fetched two MEs down and then force-landed at ANZIO. He returned to our drome flying a Kitty-Hawk. Note: The RAF continued to operate Kittyhawks in Italy until the summer of 1944 when they were finally replaced with North American Mustangs.

30 March: The Squadron's total: 52.5 enemy aircraft shot down, 18 probably shot down, 72.5 damaged.

Between April and mid-May 1944, the Squadron flew numerous sorties over the ANZIO beachhead. Enemy air activity appears to have tailed off with only occasional dogfights. However, pilots and aircraft were still lost, but more due to accidents than enemy action. Dick seems to have spent most of his time as a duty armourer. In his spare time, Dick visited Naples, went to the cinema and went swimming in the sea as the weather steadily improved.

19 May: Cassino and Monastery Hill taken. Plenty of bombers flying north during the day.

21 May: Squadron fetched eight Jerries down.

23 May: Offensive started at ANZIO. Squadron ready to move up.

3 June: ‘A’ Party packed lorries. ‘B’ Party took over Squadron kites. ‘A’ Party left camp at 19.00hrs for a drome 96 miles north.

6 June: Started to pitch camp. Heard that the Second Front has started. Rome taken. The liberation of Rome was completely overshadowed by the Normandy landings of D-Day (Operation OVERLORD).

7 June: 05.00hrs woken by anti-aircraft fire. Jerry over our drome.

8 June: Transferred to No. 8 C.C.S. (Casualty Clearing Station) six miles north of ANZIO to an airstrip called Tre Cancelli.

12 June: Packed trucks ready to move at night. Plenty of wrecked tanks on the road and bridges blown up.

13 June: 93 miles north of Rome arrived at Tarquinia (the town is situated on the coast, northwest of Rome) airfield at 03.00hrs. Passed through Rome at midnight. Wonderful buildings. Stayed about an hour in the city.

17 June: Dakotas landing all day to take away the wounded. Note: The Douglas C47 Dakota is one of the most successful military transport aircraft designs in history and was widely used by the Allies during World War Two.

22 June: Left No. 8 C.C.S. for Rome – had a tour of the city.

24 June: Moved about 60 miles north and arrived at Grosseto (another town close to the coast, northwest of Rome). The town was bomb-damaged. The R.E. (Royal Engineers) worked to repair the bomb-cratered landing strip.

4 July: Moved 50 miles north to a new airstrip. It appears from Dick’s diary that enemy air activity had dropped off considerably.

15 July: Moved about 110 miles, south to the docks.

17 July: Left harbour at 19.00hrs heading west, nine LSTs in convoy. Note: The LST or Landing Ship, Tank, was designed to carry around 18 Sherman tanks or 30 3-ton trucks and birth 200 troops. The ship could land vehicles, troops and cargo directly onto beaches without the need for a harbour.

18 July: Arrived Porto Vecchio, Corsica, at 11.00hrs. Headed north along the coast road, stopped overnight at Bastia (northern tip of Corsica).

19 July: Arrived at drome near Calvi (west of Bastia, on the coast) at 17.00hrs.

26 July: Went into Calvi in the evening and sold 200 cigarettes for 30/- (30 shillings) – a good price. You can sell almost anything here at a good price.

27 July: Getting ready for the invasion of southern France (Operation DRAGOON). 90-gallon (drop) tanks fitted to the aircraft. Pilots doing night flying and early mornings. Just the same as in Malta.

30 July – 2 August: Fighters sweep over Genoa and north.

3 August: 93 and 72 Squadrons do sweeps over Nice.

7 August: 43 Squadron pilot burned to death after belly landing and jet tank caught fire. A pilot from 225 Squadron drowned after nose-diving into Calvi Bay.

11 August: The whole Wing went on a strafing raid at 18.00hrs. They wrecked a lot of radio location stations around Nice. The mission was a complete success.

Operation DRAGOON, Invasion of southern France, 15 August – 14 September 1944

Operation DRAGOON (originally codenamed ANVIL) was an Allied invasion of southern France that led to the drive up the Rhone River Valley. Originally intended to support the D-Day invasion and Operation Overlord, DRAGOON was carried out more than two months later because of a lack of supplies and equipment. Within days, the Allies secured more than 40 miles of coastline and captured the vital French ports of Toulon and Marseille, providing critical support to the Normandy-based Allied forces moving to the German border. DRAGOON was largely an American and French operation, however, 324 Wing, including 93 Squadron provided part of the air umbrella.3

15 August: Invasion took place (start of Operation DRAGOON). Two gliders landed at the drome. A Fortress (Flying Fortress) landed shot-up by flak (A contraction of the German Flugabwehrkanone meaning anti-aircraft artillery). Kites doing air cover over the invasion beaches from dawn to dusk, but no Jerries to be seen.

21 August: Moved off for docks at 09.00hrs. Boarded LST at L'Île-Rousse (Corsica) and pulled out of the harbour at 20.00hrs. Very rough sea, the ship was rolling and pitching.

22 August: Arrived at Cavalaire (Cavalaire-sur-Mer is southwest of Nice between Saint-Tropez and Toulon in the southeast region of France) at 20.00hrs. Slept at a marshalling area outside of the town.

23 August: Left at 09.00hrs for a drome 15 miles away at St. Tropez and arrived at 11.30hrs. Departed again at 15.30hrs for a drome 140 miles north.

24 August. Terrible accident on the way down a mountain, and two died. Arrived at Cisteron (sic. Sisteron) at 20.00hrs. Marseille and Bordeaux regions of France were liberated by the Allies.

27 August – 1 September: The Squadron flew strafing sorties against enemy transport, shooting up trains, trucks, cars, etc. During this period several pilots and aircraft were lost.

5 September: Moved about 115 miles toward Lyon.

6 September: Left camp at 08.00hrs. Passed through Vienne (south of Lyon). We saw hundreds of Jerry transports burnt out along the road. Rhône valley. Arrived at Lyon airport at 16.00hrs.

8 September: The Squadron flew sweeps over Germany – strafed Jerry trucks. ‘M’ shot down in flames. F/SGT Wagstaffe killed. Flight Sergeant John William Wagstaffe, service No. 1430722, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, 93 Squadron, was killed in action flying Spitfire Mk IX MH324. He is buried in Bessey-La-Cour Churchyard, France.

22 September: Moved back to Lyon, 150 miles.

28 September: Passed through Avignon, France, and arrived at La Jass (sic. La Jasse) at 15.00hrs. Travelled 160 miles.

3 October: Moved to Marseille. Arrived at the staging area at 16.00hrs.

5 October: Boarded LST at 05.00hrs.

6 October: The boat moved out at 11.30hrs in a heavy thunderstorm. The boat was like a rocking horse.

7 October: Passed between Corsica and Sardinia at noon. Turned north for Leghorn. Note: Livorno, Italy, also known as Leghorn, which derives from the Genoese name Ligorna.

8 October: Disembarked at 18.00hrs.

During October and November, the weather in Italy steadily worsened with the airstrips often flooded, making them unserviceable (US). As no sorties could be flown for days at a time, Dick spent his time watching films and doing sentry duty.

17 – 18 November: Travelled by lorry 112 miles to Via Figliano (north of Florence) and then another 120 miles to Rimini.

20 November: Fitting bombs on the aircraft. They successfully bombed a railway.

Italy 1945

For the remainder of November, December and into January 1945, No. 93 Squadron flew interdiction missions, bombing and strafing enemy positions, infrastructure, and transport targets. Dick spent his time re-arming the Squadrons’ Spitfires. The winter weather would pause flying for days at a time. The Squadron continued to lose aircraft and pilots to enemy action and accidents.

During the early months of 1945, No. 93 Squadron mainly flew interdiction missions in support of ground operations to defeat the last pockets of German resistance in the north of Italy. On 2 May 1945, the Germans surrendered in Italy to Field Marshal Harold Alexander. On 4 May, all German forces in northwest Europe submitted to Field Marshal Montgomery. On 8 May, Victory in Europe (VE Day) was declared.

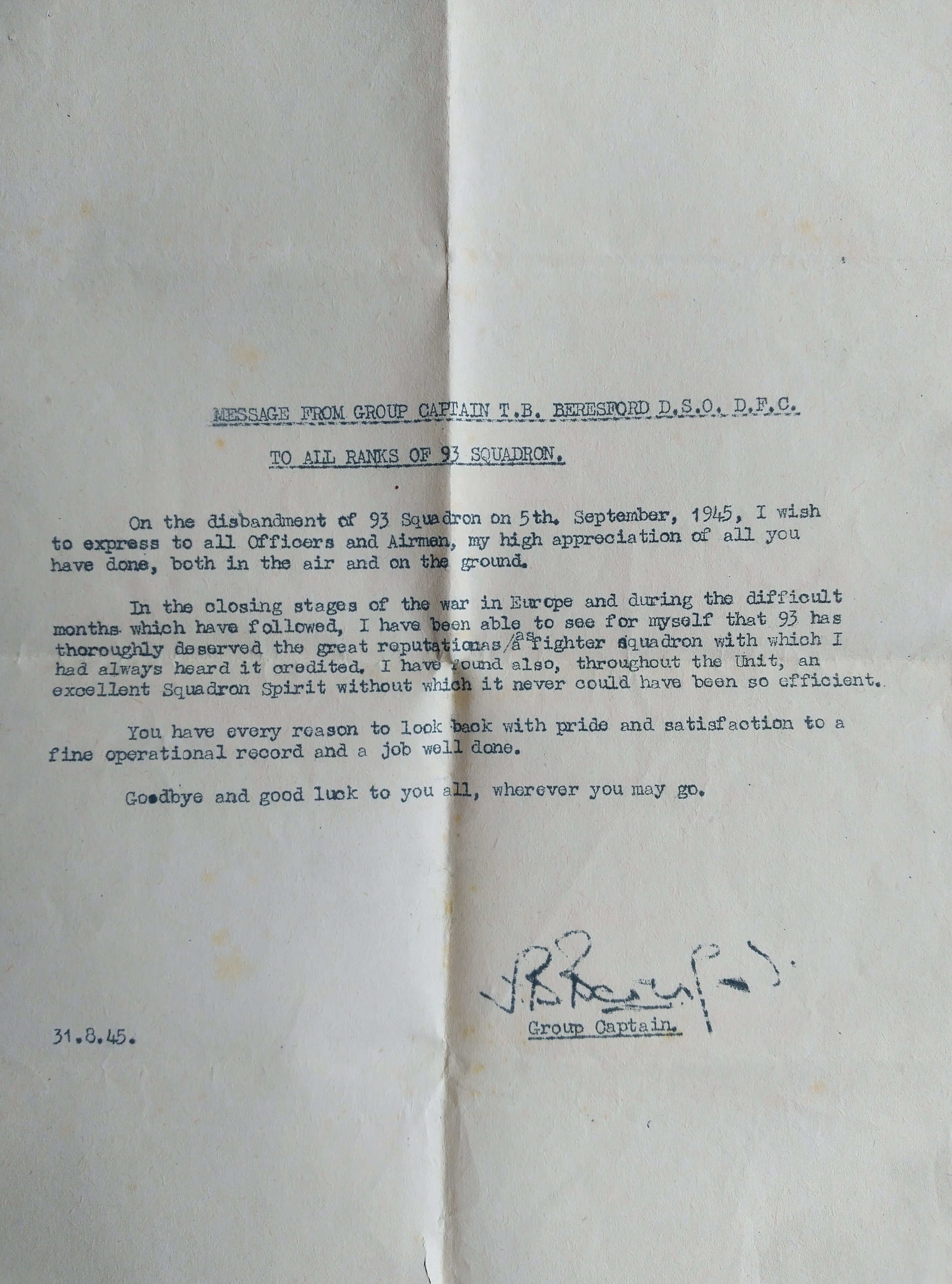

The air war in Italy cost the Allied Air Forces around 8,000 aircraft and 12,000 service personnel. They had flown 865,000 sorties and in the last seven months of the campaign had dropped around half a million tons of bombs. Immediately after VE Day, 93 Squadron moved to Klagenfurt, Austria on 15 May. On 5 September 1945, the Squadron was disbanded.

Sources:

The personal papers and diaries of Dick Hewitt, No. 93 Squadron, RAF.

Books

Evans, Bryn, The Decisive Campaigns of the Desert Air Force 1942-1945 (Pen & Sword, 2014), eBook.

Farish, Greggs, McCaul, Michael, Algiers to Anzio with 72 & 111 Squadrons (Woodfield Publishing, 2002).

Rawlings, John, Fighter Squadrons of the R.A.F. and Their Aircraft (Crecy Publishing, 1992).

Websites

1. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/01/a2055601.shtml

3. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/operation-husky

4. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/anzio-the-invasion-that-almost-failed

5. https://wikisummaries.org/operation-dragoon/

6. https://www.jeversteamlaundry.org/93squadhistory2.htm

7. https://www.keymilitary.com/article/prejudice-good-order

8. http://www.rafcommands.com/database/serials/details.php?uniq=MH324