Blog

The Second World War resulted in the deaths of around 85 million people. Additionally, tens of millions more people were displaced. However, amid all the carnage, people demonstrated remarkable courage, fortitude, compassion, mercy and sacrifice. We want to honour and celebrate all of those people. In the War Years Blog, we examine the extraordinary experiences of individual service personnel. We also review military history books, events, and museums. We also look at the history of unique World War II artefacts, medals, and anything else of interest.

How AI Can Help You Discover and Celebrate Your Military Ancestors

In this blog post, we will explore how AI can help you discover more about your military ancestors in two ways. First, AI can assist you in conducting historical research. Second, AI can now help to transform old black-and-white family photos into moving colour video footage, enabling your ancestors to tell their own stories.

If you are interested in your family history (genealogy), you may have wondered if any of your ancestors served in the military. Military service is a common and significant part of many people’s heritage, and learning more about it can enrich your understanding of your family’s past. However, finding and accessing military records can be challenging, especially if you don’t know where to look or how to interpret them. Moreover, even if you manage to find some information about your ancestor’s military service, you might still feel a gap between you and them, as you only have some names, dates, and facts, but no sense of who they were as individuals, what they looked like, what they sounded like, and how they lived. This is where AI can help.

AI, or artificial intelligence, is the ability of machines to perform tasks that normally require human intelligence, such as learning, reasoning, and problem-solving. AI has been advancing rapidly in recent years, thanks to the availability of large amounts of data and powerful computing resources. AI has many applications in various fields, including military history research and presentation.

In this blog post, we will explore how AI can help you discover more about your military ancestors in two ways. First, AI can assist you in conducting historical research. Second, AI can now help to transform old black-and-white family photos into moving colour video footage, enabling your ancestors to tell their own stories.

How AI Can Help You Conduct Historical Research

One of the main challenges of military history research is finding and accessing relevant sources. Military records are often scattered across different archives, libraries, museums, and online databases, some of which may be inaccessible or incomplete. Moreover, military records can be difficult to read and understand, as they may use unfamiliar terminology, abbreviations, symbols, or handwriting. Furthermore, military records may not provide enough information about your ancestors’ personal lives, such as their motivations, emotions, opinions, or relationships. AI can help you overcome some of these challenges by providing you with tools that can search, analyse, and synthesize large amounts of data from various sources.

For example, AI can help you:

Find and access military records that match your criteria, such as name, date of birth, place of origin, rank, unit, service number, etc.

Extract and organise relevant information from military records, such as dates, locations, events, awards, casualties, etc.

Translate and explain military terminology, abbreviations, symbols, or handwriting that may be unfamiliar or unclear to you.

Cross-reference and verify information from different sources to ensure accuracy and completeness.

Fill in the gaps or resolve the contradictions in the available information by using historical context and logic.

Generate summaries and reports of your findings that highlight the key points and provide additional details.

By using AI tools for historical research, you can save time and effort that you would otherwise spend on searching for sources manually. You can also gain a deeper and broader understanding of your ancestors’ military service by accessing more information from more sources. You can also learn more about the historical background and significance of your ancestors’ service by getting explanations and interpretations from experts. However, many archives have yet to fully digitise their collections. As a result, having to do some manual research is almost inevitable when conducting military history research.

How AI Can Help You Celebrate Your Military Ancestors

Military history research can be a fascinating journey, but it’s not always easy to share your findings in a way that is engaging and meaningful. Military records may provide some facts about your ancestors’ service, but they may not capture their personality or character. Old family photographs may give you a glimpse of what your ancestors looked like but do not convey their voice or tone. Wouldn’t it be amazing if you could see your ancestors in colour and hear them speak for themselves?

Visit our Virtual Ancestor webpage now to learn more.

Virtual Ancestor

At The War Years, we offer a new service called the Virtual Ancestor. Using the latest AI tools, we can transform a few old fading photographs into vibrant colour videos of your ancestors. Your ancestors will be able to tell their own story in the first person, based on our research of their military service. You will be able to see and hear your ancestor and learn more about their military service, their achievements, their challenges, and their personalities.

With Virtual Ancestor, you can celebrate your military ancestors in a unique and engaging way. It’s a great way to connect with your family history and learn more about your ancestors’ lives.

Contact us today, to learn more about our Virtual Ancestor and similar AI-generated historical content.

Dick Hewitt and the Desert Air Force

Dick Hewitt served as an Armourer with a mobile fighter squadron as part of the Desert Air Force (DAF) from 1943 to 1945. During Dick’s time in the RAF, he kept a diary, although this was against regulations. Although the diaries are incomplete, they have provided enough clues and information to be able to retell the wartime story of one Leading Aircraftman and his role in the Allied campaign for Italy.

Dick Hewitt served as an Armourer with a mobile fighter squadron as part of the Desert Air Force (DAF) from 1943 to 1945. During Dick’s time in the RAF, he kept a diary, although this was against regulations. Although the diaries are incomplete, they have provided enough clues and information to be able to retell the wartime story of one Leading Aircraftman and his role in the Allied campaign for Italy.

Dick Hewitt was born on Thursday 18 April 1901 in Leicester. Dick passed away on Friday 7 June 1985, aged 84, in Birmingham.

Service in the British Army

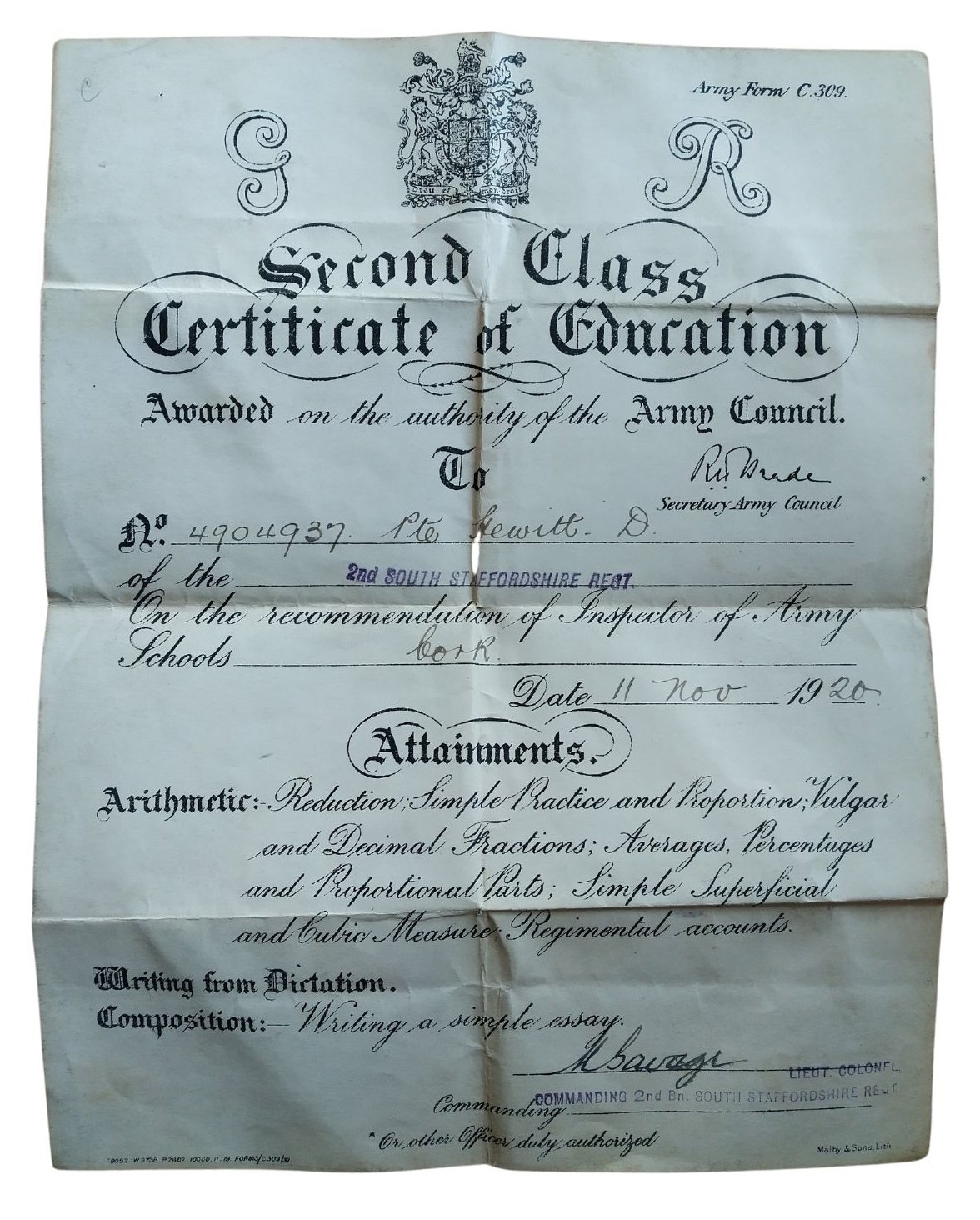

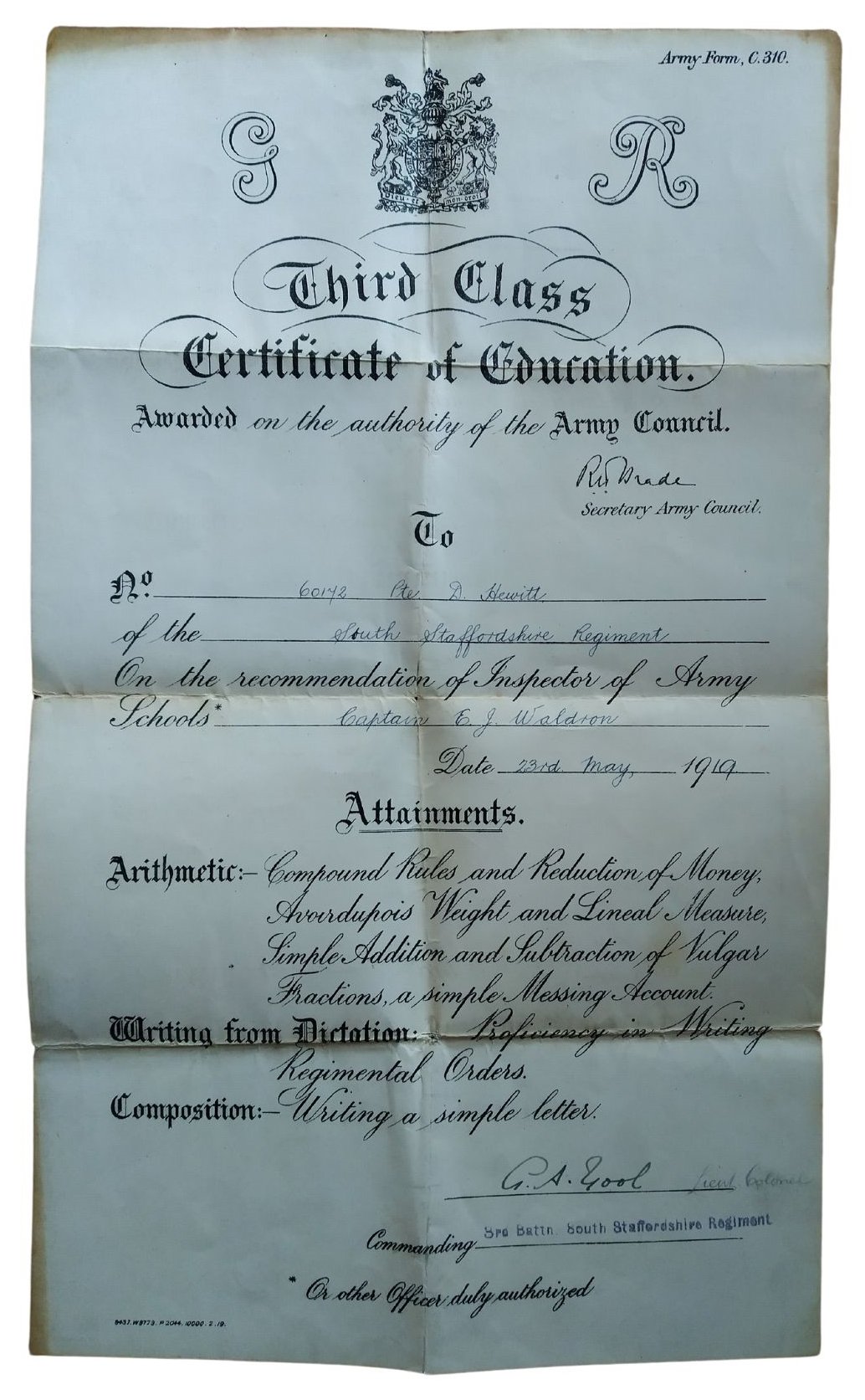

Amongst Dick’s personal papers, I found several Certificates of Education awarded to Private D. Hewitt, the 2nd Battalion, South Staffordshire Regiment issued in May 1919 and November 1920, which suggests that Dick was conscripted into the Army (as conscription did not end until mid-1919). The 2nd Battalion spent the immediate post-war years in Ireland during the War of Independence (1919-21). One of Dick’s Certificates of Education was issued from Cork, which confirms that he was stationed in Ireland. The Corps of Army Schoolmasters was replaced in 1920 by the Army Educational Corps (AEC). A brief search of The National Archives and British Army World War I Service Records, 1914-1920, found no record of Dick’s early military service with the South Staffordshire Regiment.

Dick was in his early to mid-forties during the Second World War. Most of his comrades would have been in their late teens to mid-twenties. Perhaps unsurprisingly, as an older man, it appears Dick’s comrades referred to him as ‘Pops’ based on some post-war correspondence found amongst Dick’s personal papers. Dick was married with two children while serving in the RAF and he sent money home to his family whenever he was able.

Service in the Royal Air Force

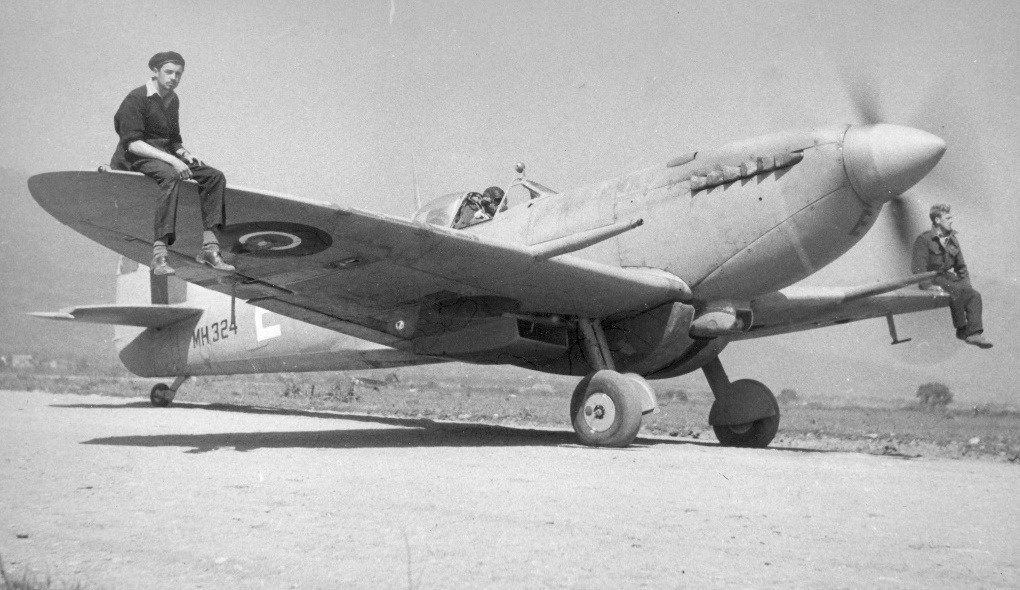

Dick’s RAF Service No: 1468728. He held the rank of Leading Aircraftman (LAC) and qualified as an Armourer. Dick served with 324 Wing, No. 93 Squadron, Royal Air Force, part of the BNAF (British North Africa Force). As part of a highly mobile fighter squadron originally equipped with Spitfire Mk. Vs and later Mk. IXs, Dick served in North Africa, Malta, Italy, Corsica, and southern France.

The Role of the Armourer

As an Armourer with No. 93 Squadron, Dick’s role was to arm the Spitfires of No. 93 Squadron with ammunition and bombs, regularly strip and clean the guns and perform general maintenance. Based on Dick’s diary entries, he also worked on fitting supplementary fuel tanks to the Spitfires, which extended their range.

Diary Entries: UK Training & Posting Overseas 1942

9 January: Left Halton Camp for Kirkham. RAF Halton, near Wendover, Buckinghamshire, was a major RAF training centre. Similarly, RAF Kirkham, Lancashire, was the main armament training centre for the RAF from November 1941.

1942: Passed Armourer’s course, A.C. II. – Aircraftman 2nd class.

30 March 1942: Passed L.A.C. exam – Leading Aircraftsman.

1942: Arrived at RAF Speke. Note: Today, RAF Speke is Liverpool John Lennon Airport.

1942: Promoted A.C. I. - Aircraftman 1st class.

11 November: Left Wareford for overseas. By train to Scotland. Arrived at Greenock at 08.00hrs.

13 November: Boarded the HMT (His Majesty's Transport) Bergensfjord (a former Norwegian ocean liner). Navy, Army, and Air Force personnel were all on board.

14 November: Left Greenock at 05.00hrs heading for the North Atlantic. There are 16 boats in our convoy escorted by Royal Navy Destroyers.

20 November: Nearing the Mediterranean, passed Gib (Gibraltar) at midnight. Could see Tangiers lit up at night.

Tunisia 1942

8 December: Arrived at Souk-El-Arba station (Tunisia) at 08.00hrs. We’re about 40 miles behind the frontline.

19 December: Had a terrible sight to witness as one of the (ditto) ground crews was taken up in the air sitting on the tail of a plane. The kite (RAF slang for aircraft) crashed on landing throwing the man right over the front of the kite. He sustained serious injuries to his legs. Note: During bad or windy weather, it was common practice to have a member of the groundcrew sit on the tailplane of an aircraft as it taxied to its take-off position. Usually, the groundcrew would dismount while the pilot carried out their pre-flight checks.

30 December: Nearly killed when strafed by a Jerry aircraft. Had to dive for cover on the roadside. Learned all the Squadron’s tools were lost when the boat carrying them was torpedoed on 18 December.

The Desert Air Force (DAF) in Tunisia

The Allied campaign in Tunisia started in November 1942. By late March and throughout April 1943, the Desert Air Force (DAF) was conducting bombing and strafing missions (interdiction) on infrastructure, such as bridges, supply routes, Luftwaffe airbases, Tunisian ports, and the capital of Tunis. They also flew missions over Sicily and southern Italy. The aim of the missions was twofold. First, starve Axis forces of everything from fuel and ammunition to food, and thus weaken their ability to resist. The second was to establish Allied air superiority over the battle space and enable the ground forces to make a final push on the Tunisian capital. The DAF also provided close air support to Allied ground forces.

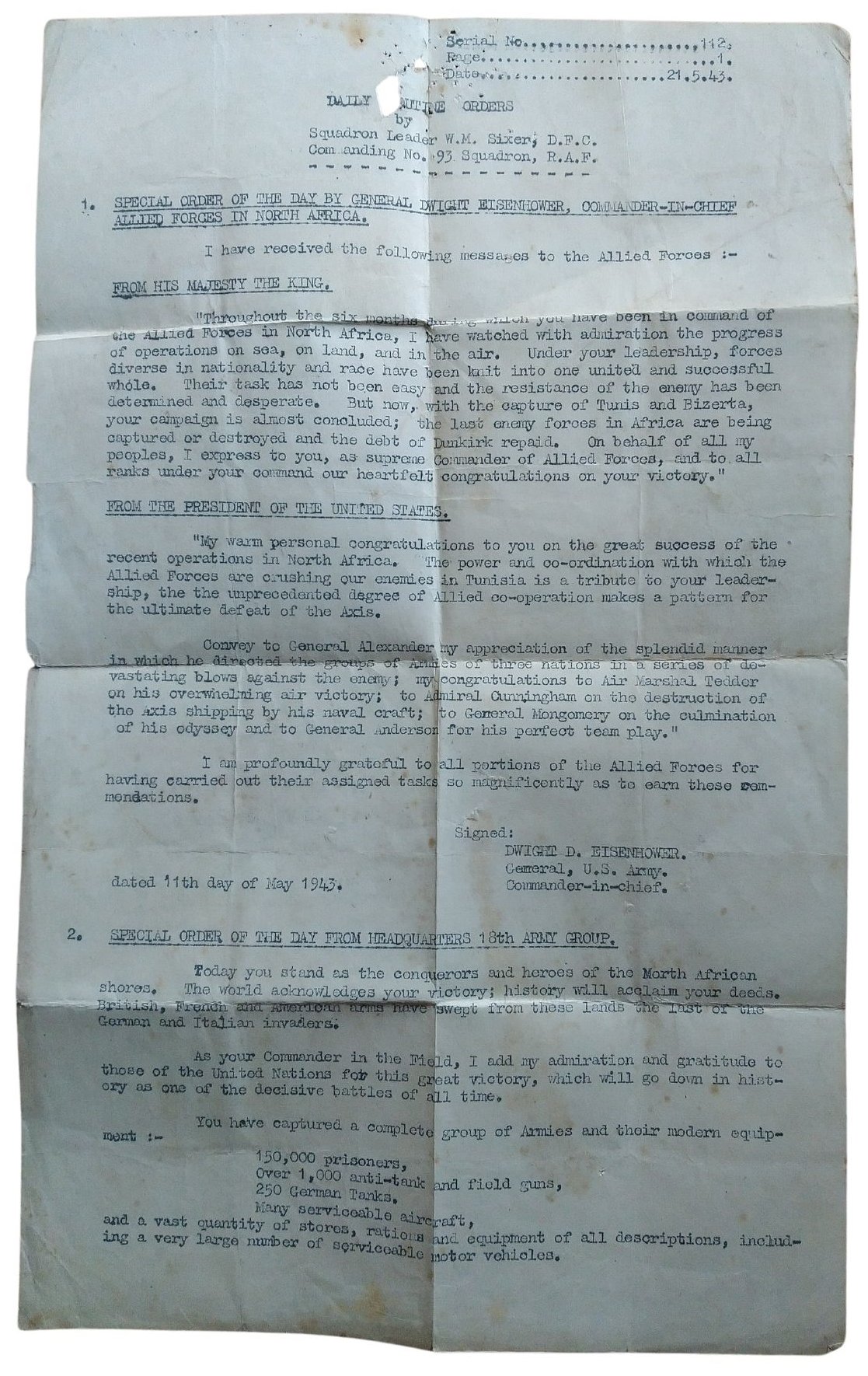

On 7 May 1943, Allied armour rolled into Tunis, taking many Axis troops based in the city completely by surprise. By 10 May, the Luftwaffe had evacuated what aircraft and equipment they could salvage. The capture of Tunis led to an Axis surrender and the capture of around 250,000 prisoners. It was a significant Allied victory.

No 72 Squadron, 324 Wing RAF. Spitfire, North Africa 1943.

Diary Entries: Tunisia 1943

3 February 1943: Jerry bombed drome (aerodrome) in the morning. Three RAF were killed and five wounded. Bombs were released from FWs (Focke Wulf 190 fighter-bombers) while I was having a wash. Eight Spits U.S. (unserviceable).

22 February 1943: Fortresses (B.17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber) dropped bombs on Souk-El-Arba, 25 people killed by mistake. Note: There were two airfields at Souk-El-Arba both located near what was at the time the village of Souk-El-Arba but since 1966 has been known as Jendouba. The site is about 81 miles west-southwest of Tunis.

1 March 1943: Kites on a bomber escort, one Spit and one ME (presumably a Messerschmitt Bf 109) shot down during a dogfight over the drome at 12.30hrs.

2 March 1943: Air Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham arrived at the drome. Note: Today, Coningham is chiefly remembered as the person most responsible for the development of forward air control parties directing close air support, which he developed as commander of the Western Desert Air Force between 1941 and 1943.

16 March 1943: Dive-bombed without warning. Dived under a kite and watched bombs bursting. AA (anti-aircraft artillery) returned fire. One soldier was killed.

April 1943: Squadron mainly assigned to bomber escort missions. Note: The Allies heavily bombed Axis (Luftwaffe and Italian) airfields and infrastructure such as bridges. Enemy air activity diminished as the Allies' bombing campaign intensified.

7 May: Tunis reported taken.

10 May: Bizerta reported taken. After being reported missing Red Herbert got back to the airfield with 20 released prisoners.

12 May: Thousands of prisoners taken. End of the campaign in Africa.

14 May: Move to a new drome between Tunis and Bizerta. Met thousands of prisoners and passed through the battlefront. Saw plenty of wrecked tanks, etc.

15 May: On new drome. Found a camp bed, very useful. Bags of rifles, etc. Crashed and wrecked Ju-52s all over the airfield and two ME-109s. Had to be careful of boobytraps and mines. Note: The Junkers Ju-52 is a three-engine transport aircraft and was a mainstay of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe).

20 May: Victory Parade at Tunis. Thousands of troops were in the town.

24 May: Went souvenir hunting. Found the famous Ace of Spades Squadron drome. Every kite was either burned out or shot up. Bags of stores lying about. In this diary entry, Dick is referring to the Jagdgeschwader 53 (JG 53) fighter-wing of the Luftwaffe, known as the "Pik As" (Ace of Spades).

26 May: Move to a drome at Mateur, which is situated between Bizerta and Tunis.

8 June: Drove to Sfax harbour (south of Tunis) and boarded a Landing Ship, Tank (LST).

9 June: Arrived in Malta.

Dick Hewitt, on the left, sitting on the wing of a Spitfire. Date and location of photograph unknown.

Malta 1943

20 June: The King arrived in Malta. He visited the drome.

24 June: Sir Archibald Sinclair (Secretary of State for Air) visited the drome in the afternoon and gave a speech. He thanked us for our work in North Africa.

10 July: Operation HUSKY. Sicily was invaded by troops at 02.30hrs. Kites on dawn sweeps (sorties) over Sicily. Worked until 23.00hrs.

Operation HUSKY, Allied Invasion of Sicily, 9 July - 17 August 1943

Prior to an Allied invasion of the Italian mainland, it was necessary to capture the island of Sicily. Axis forces based on Sicily were resupplied across the Messina Strait. The key target of the invasion was the port of Messina, the link to the Italian mainland. But it was heavily defended and its distance from North Africa meant the Allies could not attack it directly.

A major concern and threat to the invasion fleet was the Italian island of Pantelleria, about 50 miles from the Tunisian coast and halfway to Sicily. The island could be used by Axis forces to attack the invasion fleet at sea. Consequently, the island was heavily bombed and then shelled by the navy. Finally, on 11 June 1943, British troops landed at the main harbour, and the island garrison surrendered.

During June and July 1943, the Desert Air Force started to relocate to Malta in preparation for the invasion of Sicily.

On 9 July, British, Commonwealth and American troops started landing on Sicily preceded by airborne forces. In the weeks prior to the invasion, the Allies had launched a concerted aerial bombardment of the Axis air forces on Sicily – winning air superiority. However, bad weather on the night of 9 July resulted in the airborne forces being scattered. Once ashore, the British 8th Army initially made steady progress north until checked at Catania. The Americans, under General Patton, took Palermo. After fighting a defensive campaign for about two weeks, the Axis forces started to withdraw. After 38 days, Allied forces finally took Messina. However, around 120,000 enemy troops had been successfully evacuated. At the time, Operation HUSKY was the largest amphibious invasion of the Second World War with over 180,000 men, 4,000 aircraft, and 3,000 vessels deployed.1

Italy 1943

19 – 20 July: Moved by tank landing craft to Sicily. Arrived Pachino beach (southern tip of Sicily) at 06.00hrs.

12 August: Jerry bombed Lentini Drome (south of Catania) during the night (surprise raid) 24 kites were written off, and 96 airmen were killed or wounded (322 Wing).

13 August: Jerry retreats toward Messina evacuating troops.

17 August: Messina reported taken.

18 August: End of Sicilian Campaign.

27 August: Moved to Gerbibi near Mount Etna (west of Catania).

7 September: Arrived Falcone (north coast of Sicily).

Operation AVALANCHE – Allied landings at Salerno, 8/9 September 1943

German forces correctly anticipated the Allied landings near the port of Salerno by the U.S. 5th Army and concentrated five divisions against the beachhead. Initially, it appeared the Allies might be thrown back into the sea. However, Allied airpower gradually strangled the Germans' ability to resupply its land forces, and gradually they had to give ground. However, the Germans exploited the mountainous terrain to their full advantage as they staged a fighting withdrawal northward. Eventually, Allied progress was brought to a halt along the heavily fortified ‘Gustav Line’.

8 September: We were told landings would be made near Naples during the night (Operation AVALANCHE). Ready to move to Naples. Italy surrendered and Naples invaded in the early hours.

During the next few days, the Squadron flew numerous sorties over the beachhead providing air support to the ground forces.

23 September: Moved to Milazzio (west of Messina) and boarded transport, moved off at 20.30hrs headed for the Italian mainland.

24 September: Convoy shelled. Landed midday near Salerno.

28 September: Moved to Battipaglia drome (east of Salerno).

11 October: Moved to Naples passing through Pompei.

30 October: Air Chief Marshal Sir Keith Park landed at Drome. Note: Park played a pivotal role in winning the Battle of Britain.

Usually, a Spitfire Squadron had twelve aircraft split into two flights of six (A and B Flights). In combat, the aircraft would typically divide into smaller groups of two or three aircraft.

12 November: German fighter bombers attacked a nearby airfield. The Squadron’s aircraft were scrambled and pursued the enemy aircraft, but they escaped.

14 November: 324 Wing broke the record for the number of kites shot down in 12 months: 301.5.

22 November: Enemy aircraft strafed the main road to Rome. Six enemy aircraft were shot down and another six were probably downed.

24 November: Six aircraft on shipping patrol and ‘L’ on patrol of the front line (presume that the letter ‘L’ refers to an individual aircraft).

26 November: A German Ju-88 (The Junkers Ju-88 twin-engine multirole combat aircraft) was shot down by 435 Squadron. Kites on mine sweeping patrol. Enemy aircraft over our drome and heavy AA fire (anti-aircraft artillery sometimes referred to by the British and Commonwealth forces as Ack-Ack).

28 November: Strafed road transport – four trucks and two staff cars hit. F/O (Flying Officer - a junior commissioned rank in the Royal Air Force) Swain dived too low, hit some trees, and then went straight into the ground.

2 December: Kites on bomb line patrol. Note: The bomb line is a line or limit beyond which aircraft may make attacks on the enemy without risking damage to their own troops.

5 December: Kit bags lost at BARI (Bari is a port city on the Adriatic Sea and the capital of southern Italy’s Puglia region). 12 ships sunk in the harbour. Souvenirs, etc. all lost, and 500 Woodbines (British brand of cigarettes).

7 December: Red Herbert shot down a Me-109, his first kill. Note: The Messerschmitt Bf 109 was the backbone of the Luftwaffe’s fighter force along with the Focke-Wulf Fw-190. Me-109 and Bf-109 are used interchangeably to refer to the aircraft.

10 December: Jet tanks fitted. Note: I am assuming this diary entry refers to the ground crew fitting jettisonable extra fuel tanks to the Spitfires. These fuel tanks extended the range a Spitfire could fly but also somewhat limited the aircraft’s performance. The fuel tanks were fitted under the central section of the fuselage and carried a 30, 45 or 90-gallon capacity. They were also known as drop tanks or ‘slipper’ tanks and could be jettisoned after use or before engaging enemy aircraft.

16 December: FLT (Flight Lieutenant) Taylor was shot down and belly-landed on a beach. Returned safely the next day.

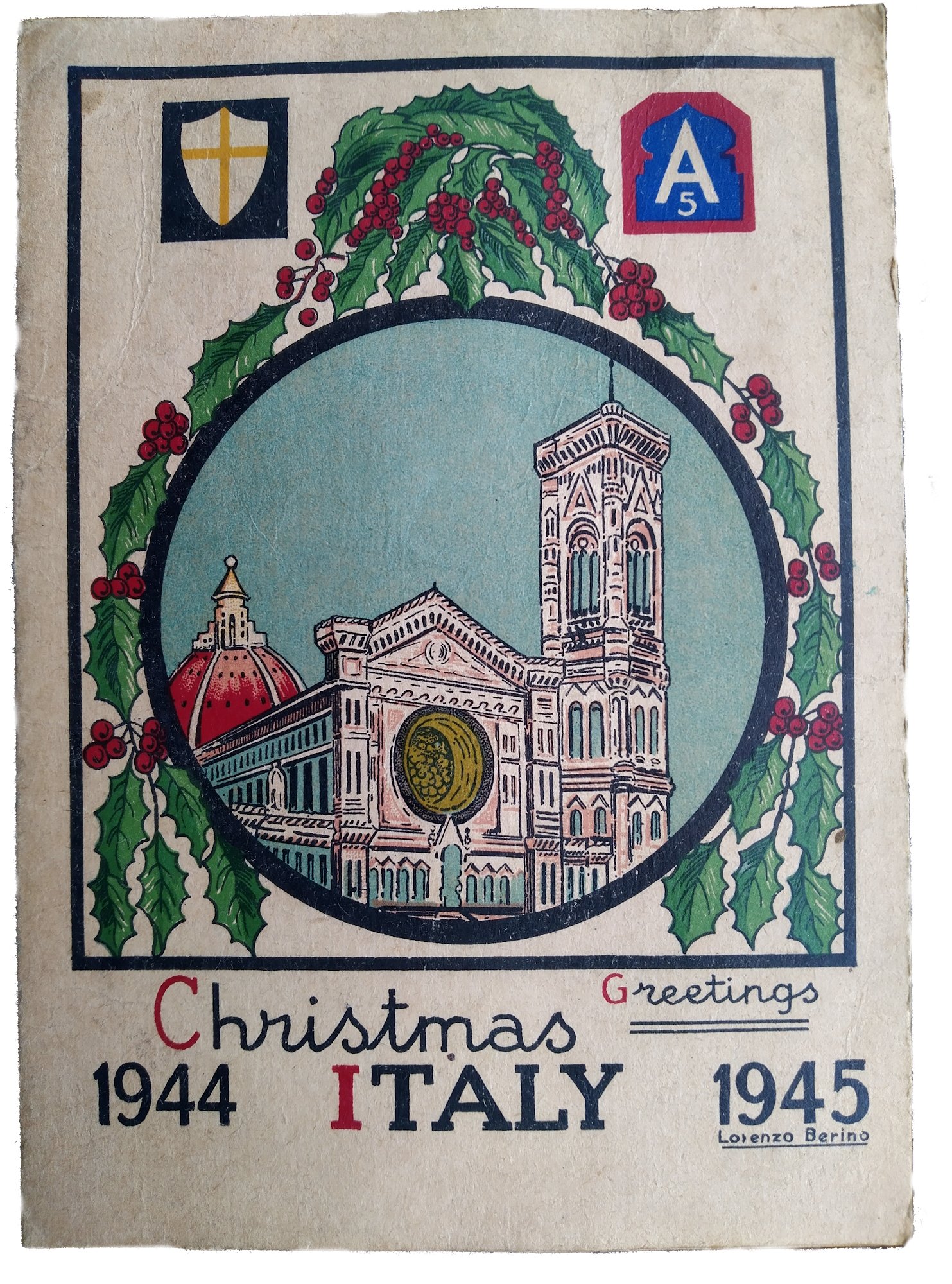

Christmas: Dick seems to have enjoyed the Christmas period with plenty to eat and drink. He complained of feeling hungover on Christmas day after too much merry-making the night before.

The weather during the late autumn and early winter of 1943/44 steadily deteriorated. The Squadron was often at half-hour readiness (held ready to scramble into action if required). When not working, Dick appears to have spent much of his free time visiting local towns, going to the cinema and the occasional concert, and following the inter-squadron football matches. He was also assigned to sentry duty.

Italy 1944

11 January: Typhus is very bad in Naples.

13 January: Bombers over all day (Flying Fortresses) about 950 passed overhead on their way to bomb Cassino (Between 17 January and 18 May, Monte Cassino and the Gustav Line defences were attacked on four occasions by Allied troops.). All fives went away replaced by nines. Note: Dick is referring to the replacement of Mk. V Spitfires with the new Mk. IX variant.

14-16 January: Prepared to move to a new location. Left Naples at 10.30hrs and arrived at the new drome about 14.00hrs. Crossed the Volturno River Bridge.

18 January: Watched Bostons drop their loads on enemy positions and return safely. In this diary entry, Dick is referring to the American-built Douglas A-20 Havoc medium bomber that was renamed the Boston by the RAF.

19 January: 15 miles behind front lines – guns firing.

Operation SHINGLE, the Battle of Anzio, 22 January – 5 June 1944

To break the deadlock and get the Allied advance moving again, the High Command decided to launch another amphibious landing. The intention of Operation SHINGLE was to bypass the Gustav Line, forcing the Germans to pull troops back from Cassino and open the road to Rome. Operation SHINGLE was launched on 22 January 1944. Initially, the landings were unopposed. However, the Allies quickly lost the initiative and failed to break out from the beachhead. Instead, by 25 January, the Germans counterattacked with elements of five divisions and quickly surrounded the Allied landing force. For months, the Anzio campaign dragged on with neither side able to gain a significant advantage. Eventually, the deadlock was broken when the Allies launched a series of new operations compelling the Germans to redeploy their limited forces. On 4/5 June, Rome fell, but the Germans remained undefeated and pulled back to a new defensive position known as the Gothic Line.2

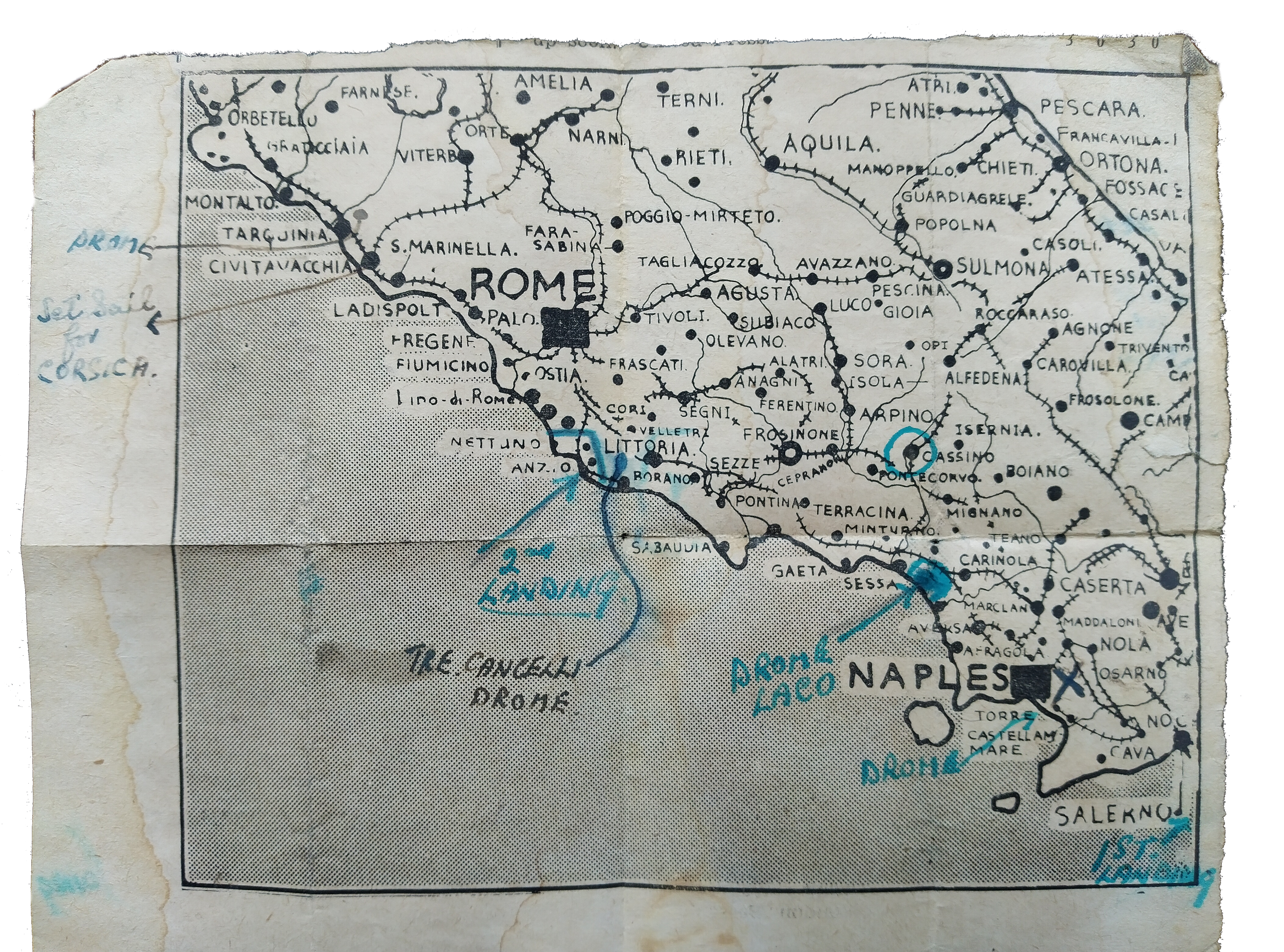

21 January: Told that another landing would be made 50 miles north of here during the night at Cape ANZIO.

22 January: Landings successful – no opposition. Went to the village of Mondragone (situated on the coast about 28 miles northwest of Naples). The village had been badly bombed.

27 January: The Squadron fetched four down and two damaged for the loss of one pilot missing. Dick often uses the term ‘fetched down’ in his diaries to indicate that the Squadron had either shot down or damaged enemy aircraft.

28 January: The Squadron is down to six serviceable aircraft due to prangs. Plenty of shelling night and day. Note: The loss of aircraft due to non-operational accidents seemed common at the time. Between 1939 and 1945 RAF Bomber Command, for example, lost 1,380 aircraft within the UK on operational flights and 3,986 aircraft in non-operational accidents.

7 February: Two MEs (Messerschmitt Bf 109s) shot down. Red Herbert forced landing with serious injuries.

10 February: Cruisers shelling enemy positions night and day.

12 February: Jerry active over ANZIO beach, bombing and strafing.

15 February: Red Herbert died in hospital. Note: In fact, Flight Sergeant Henry Ivor (Red) Herbert, Service Number: 415189, 93 Sqdn., Royal New Zealand Air Force, died on 7 February 1944, age 20. Red is buried at the Anzio War Cemetery. He had been flying Spitfire Mk. IX MA509.

16-17 February: Dick says the Wing shot down seven enemy aircraft over the ANZIO beachhead. He also writes that ‘R’ and ‘Z’ both had forced landings at ANZIO. I am assuming that Dick is referring to individual aircraft using the RAF letter code. The RAF used three-letter codes to identify aircraft from a distance. Two letters before the roundel, for the squadron to which the aircraft belonged, and another letter after the roundel for the individual aircraft.

1 March: Record of enemy kites destroyed 343.5.

16 March: Cassino was heavily bombed for two days.

18 March: Went on a day trip to Napoli (Naples). Returning at night saw Mount Vesuvius in eruption. Most wonderful sight to see. Hot lava running down the sides. Still visible at 30 miles. The volcanic eruption had started the day before and lasted for about ten days.

22 March: Mount Vesuvius – People have started to evacuate southern Naples.

23 March: Finished work at 17.00hrs and went on a trip to see Mount Vesuvius at night. A sight worth seeing.

24 March: W/O (Warrant Officer) Bunting fetched two MEs down and then force-landed at ANZIO. He returned to our drome flying a Kitty-Hawk. Note: The RAF continued to operate Kittyhawks in Italy until the summer of 1944 when they were finally replaced with North American Mustangs.

30 March: The Squadron's total: 52.5 enemy aircraft shot down, 18 probably shot down, 72.5 damaged.

Between April and mid-May 1944, the Squadron flew numerous sorties over the ANZIO beachhead. Enemy air activity appears to have tailed off with only occasional dogfights. However, pilots and aircraft were still lost, but more due to accidents than enemy action. Dick seems to have spent most of his time as a duty armourer. In his spare time, Dick visited Naples, went to the cinema and went swimming in the sea as the weather steadily improved.

19 May: Cassino and Monastery Hill taken. Plenty of bombers flying north during the day.

21 May: Squadron fetched eight Jerries down.

23 May: Offensive started at ANZIO. Squadron ready to move up.

3 June: ‘A’ Party packed lorries. ‘B’ Party took over Squadron kites. ‘A’ Party left camp at 19.00hrs for a drome 96 miles north.

6 June: Started to pitch camp. Heard that the Second Front has started. Rome taken. The liberation of Rome was completely overshadowed by the Normandy landings of D-Day (Operation OVERLORD).

7 June: 05.00hrs woken by anti-aircraft fire. Jerry over our drome.

8 June: Transferred to No. 8 C.C.S. (Casualty Clearing Station) six miles north of ANZIO to an airstrip called Tre Cancelli.

12 June: Packed trucks ready to move at night. Plenty of wrecked tanks on the road and bridges blown up.

13 June: 93 miles north of Rome arrived at Tarquinia (the town is situated on the coast, northwest of Rome) airfield at 03.00hrs. Passed through Rome at midnight. Wonderful buildings. Stayed about an hour in the city.

17 June: Dakotas landing all day to take away the wounded. Note: The Douglas C47 Dakota is one of the most successful military transport aircraft designs in history and was widely used by the Allies during World War Two.

22 June: Left No. 8 C.C.S. for Rome – had a tour of the city.

24 June: Moved about 60 miles north and arrived at Grosseto (another town close to the coast, northwest of Rome). The town was bomb-damaged. The R.E. (Royal Engineers) worked to repair the bomb-cratered landing strip.

4 July: Moved 50 miles north to a new airstrip. It appears from Dick’s diary that enemy air activity had dropped off considerably.

15 July: Moved about 110 miles, south to the docks.

17 July: Left harbour at 19.00hrs heading west, nine LSTs in convoy. Note: The LST or Landing Ship, Tank, was designed to carry around 18 Sherman tanks or 30 3-ton trucks and birth 200 troops. The ship could land vehicles, troops and cargo directly onto beaches without the need for a harbour.

18 July: Arrived Porto Vecchio, Corsica, at 11.00hrs. Headed north along the coast road, stopped overnight at Bastia (northern tip of Corsica).

19 July: Arrived at drome near Calvi (west of Bastia, on the coast) at 17.00hrs.

26 July: Went into Calvi in the evening and sold 200 cigarettes for 30/- (30 shillings) – a good price. You can sell almost anything here at a good price.

27 July: Getting ready for the invasion of southern France (Operation DRAGOON). 90-gallon (drop) tanks fitted to the aircraft. Pilots doing night flying and early mornings. Just the same as in Malta.

30 July – 2 August: Fighters sweep over Genoa and north.

3 August: 93 and 72 Squadrons do sweeps over Nice.

7 August: 43 Squadron pilot burned to death after belly landing and jet tank caught fire. A pilot from 225 Squadron drowned after nose-diving into Calvi Bay.

11 August: The whole Wing went on a strafing raid at 18.00hrs. They wrecked a lot of radio location stations around Nice. The mission was a complete success.

Operation DRAGOON, Invasion of southern France, 15 August – 14 September 1944

Operation DRAGOON (originally codenamed ANVIL) was an Allied invasion of southern France that led to the drive up the Rhone River Valley. Originally intended to support the D-Day invasion and Operation Overlord, DRAGOON was carried out more than two months later because of a lack of supplies and equipment. Within days, the Allies secured more than 40 miles of coastline and captured the vital French ports of Toulon and Marseille, providing critical support to the Normandy-based Allied forces moving to the German border. DRAGOON was largely an American and French operation, however, 324 Wing, including 93 Squadron provided part of the air umbrella.3

15 August: Invasion took place (start of Operation DRAGOON). Two gliders landed at the drome. A Fortress (Flying Fortress) landed shot-up by flak (A contraction of the German Flugabwehrkanone meaning anti-aircraft artillery). Kites doing air cover over the invasion beaches from dawn to dusk, but no Jerries to be seen.

21 August: Moved off for docks at 09.00hrs. Boarded LST at L'Île-Rousse (Corsica) and pulled out of the harbour at 20.00hrs. Very rough sea, the ship was rolling and pitching.

22 August: Arrived at Cavalaire (Cavalaire-sur-Mer is southwest of Nice between Saint-Tropez and Toulon in the southeast region of France) at 20.00hrs. Slept at a marshalling area outside of the town.

23 August: Left at 09.00hrs for a drome 15 miles away at St. Tropez and arrived at 11.30hrs. Departed again at 15.30hrs for a drome 140 miles north.

24 August. Terrible accident on the way down a mountain, and two died. Arrived at Cisteron (sic. Sisteron) at 20.00hrs. Marseille and Bordeaux regions of France were liberated by the Allies.

27 August – 1 September: The Squadron flew strafing sorties against enemy transport, shooting up trains, trucks, cars, etc. During this period several pilots and aircraft were lost.

5 September: Moved about 115 miles toward Lyon.

6 September: Left camp at 08.00hrs. Passed through Vienne (south of Lyon). We saw hundreds of Jerry transports burnt out along the road. Rhône valley. Arrived at Lyon airport at 16.00hrs.

8 September: The Squadron flew sweeps over Germany – strafed Jerry trucks. ‘M’ shot down in flames. F/SGT Wagstaffe killed. Flight Sergeant John William Wagstaffe, service No. 1430722, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, 93 Squadron, was killed in action flying Spitfire Mk IX MH324. He is buried in Bessey-La-Cour Churchyard, France.

22 September: Moved back to Lyon, 150 miles.

28 September: Passed through Avignon, France, and arrived at La Jass (sic. La Jasse) at 15.00hrs. Travelled 160 miles.

3 October: Moved to Marseille. Arrived at the staging area at 16.00hrs.

5 October: Boarded LST at 05.00hrs.

6 October: The boat moved out at 11.30hrs in a heavy thunderstorm. The boat was like a rocking horse.

7 October: Passed between Corsica and Sardinia at noon. Turned north for Leghorn. Note: Livorno, Italy, also known as Leghorn, which derives from the Genoese name Ligorna.

8 October: Disembarked at 18.00hrs.

During October and November, the weather in Italy steadily worsened with the airstrips often flooded, making them unserviceable (US). As no sorties could be flown for days at a time, Dick spent his time watching films and doing sentry duty.

17 – 18 November: Travelled by lorry 112 miles to Via Figliano (north of Florence) and then another 120 miles to Rimini.

20 November: Fitting bombs on the aircraft. They successfully bombed a railway.

Italy 1945

For the remainder of November, December and into January 1945, No. 93 Squadron flew interdiction missions, bombing and strafing enemy positions, infrastructure, and transport targets. Dick spent his time re-arming the Squadrons’ Spitfires. The winter weather would pause flying for days at a time. The Squadron continued to lose aircraft and pilots to enemy action and accidents.

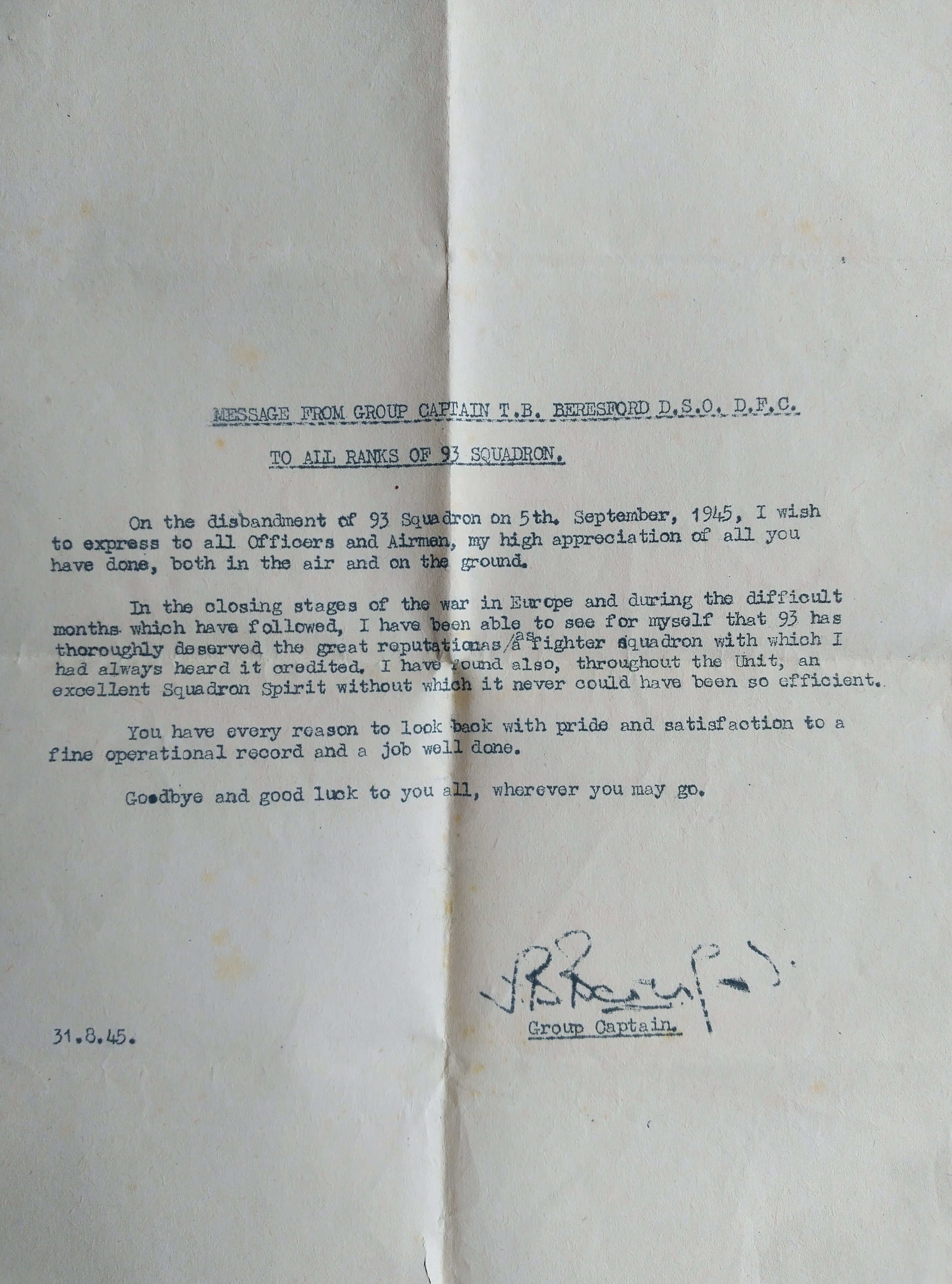

During the early months of 1945, No. 93 Squadron mainly flew interdiction missions in support of ground operations to defeat the last pockets of German resistance in the north of Italy. On 2 May 1945, the Germans surrendered in Italy to Field Marshal Harold Alexander. On 4 May, all German forces in northwest Europe submitted to Field Marshal Montgomery. On 8 May, Victory in Europe (VE Day) was declared.

The air war in Italy cost the Allied Air Forces around 8,000 aircraft and 12,000 service personnel. They had flown 865,000 sorties and in the last seven months of the campaign had dropped around half a million tons of bombs. Immediately after VE Day, 93 Squadron moved to Klagenfurt, Austria on 15 May. On 5 September 1945, the Squadron was disbanded.

Sources:

The personal papers and diaries of Dick Hewitt, No. 93 Squadron, RAF.

Books

Evans, Bryn, The Decisive Campaigns of the Desert Air Force 1942-1945 (Pen & Sword, 2014), eBook.

Farish, Greggs, McCaul, Michael, Algiers to Anzio with 72 & 111 Squadrons (Woodfield Publishing, 2002).

Rawlings, John, Fighter Squadrons of the R.A.F. and Their Aircraft (Crecy Publishing, 1992).

Websites

1. https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/stories/01/a2055601.shtml

3. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/operation-husky

4. https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/anzio-the-invasion-that-almost-failed

5. https://wikisummaries.org/operation-dragoon/

6. https://www.jeversteamlaundry.org/93squadhistory2.htm

7. https://www.keymilitary.com/article/prejudice-good-order

8. http://www.rafcommands.com/database/serials/details.php?uniq=MH324

HURRICANE: The poignant biography of the plane that won the war.

HURRICANE: The Plane That Won the War by Jacky Hyams tells the story of the Hawker Hurricane and the people who designed it, built it, fought in it, and maintained and repaired it. Read the full book review now.

One British aircraft of the Second World War has come to symbolize the indomitable spirit of the nation during the dark days of 1940, the Supermarine Spitfire. However, it was the Hawker Hurricane that shot down more than half of the Luftwaffe’s raiders during the Battle of Britain. In Jacky Hyams’s new book, HURRICANE: The Plane That Won the War, published by Michael O’Mara Books Limited, the bestselling author attempts to set the record straight.

HURRICANE is an account of how the aircraft was designed, built and its service history. The book is also a testament to the pilots, the Air Transport Auxiliary, the ground crews, and the many unsung heroes of the production line. The stubby Hawker Hurricane or ‘Hurri’ as it was affectionately known was the brainchild of entrepreneurial aircraft manufacturer Sir Tommy Sopwith and Chief Designer, Sir Sydney Camm. Today, Camm is largely forgotten while the name of R.J. Mitchell, the designer of the Spitfire, is familiar to many. Yet, Camm would lead the design teams of the Hawker Typhoon, Hawker Tempest, and the post-war marvel, the Hawker Siddeley Harrier ‘jump jet’.

The Hurricane was the first monoplane fighter to enter service with the RAF, although the Bristol M1 was briefly in service at the end of the First World War. Partially constructed from wood and canvas, the Hurricane was quicker and cheaper to manufacture than its more glamorous stable mate, the Spitfire. The Hurri was also a more rugged aircraft, capable of withstanding Luftwaffe punishment that the Spitfire could not. The aircraft’s simple design meant that during the critical days of the Battle of Britain, seemingly unrepairable planes were patched up and put back into service by maintenance units. By the 15th of September 1940, the Hawker Hurricane had shot down more enemy aircraft than all other types of RAF aircraft and anti-aircraft (AA) guns put together.

Using a combination of archive materials and first-hand accounts, Jacky Hyams’s book retells more than just the history of the Hawker Hurricane. It is a book about the countless human stories of quiet courage, sacrifice, hard work, and emotional strain that the factory workers, pilots, and ground crews endured throughout the Second World War. The author keeps the technical jargon and military acronyms to a minimum, and when used she provides short, concise explanations.

Over the post-war period, the Hurri has proven fertile ground for authors, historians, and aircraft enthusiasts with over a hundred books and articles published on the subject. So, it might be fair to say there isn’t too much new to say about the fighter. Nevertheless, Jacky Hyams’s book is engaging, easy to read, poignant, and informative in turn.

By the end of its operational life, the Hawker Hurricane had served in every major theatre of the Second World War and flown with numerous air forces from Australia to Yugoslavia. Around 25 different variants of the aircraft were eventually produced, from Hawker Sea Hurricane to tank-busting ground attack aircraft. Together with the countless men and women who gave themselves so tirelessly to defeat tyranny perhaps Sir Sydney Camm’s stubby little aircraft, the Hawker Hurricane, was the plane that won the war.

SAS Battle Ready by Dominic Utton – a compendium of forty Special Air Service operations

In this book review, we examine SAS Battle Ready by Dominic Utton – a compendium of forty Special Air Service operations.

SAS Battle Ready is the latest book from journalist and author Dominic Utton. The book is an anthology of forty Special Air Service (SAS) operations since the unit’s formation in 1941.

The book is divided into three sections. The first section, Forged in War, briefly explains the early history of the SAS from inception during the North Africa campaign to Operation Archway three and a half years later. The next section of the book examines the period between 1952 and 2000. During this period the SAS evolved with the changing nature of global threats from the decline of the British Empire to the rise of international terrorism and hostage-taking. During this time, SAS operations spanned Malaya, Oman, Somalia, the Iranian Embassy siege, London, and the Falklands War. Finally, the book concludes with the Regiment’s most recent operations in Iraq and Afghanistan as part of the post-9/11 so-called War on Terror.

Perhaps due to his background in journalism, Dominic Utton has a talent for being able to summarise some of the world’s most complex conflicts in just a few brief sentences. In fact, he succeeds in telling the dramatic story of forty SAS operations from the early ‘shoot-and-scoot’ missions across the Libyan Desert to hunting for Scud missile launchers in Iraq with remarkable economy. The book also contains some fascinating facts, such as the SAS suffered 330 casualties during the Second World War while they manage to inflict around 31,000 losses on Axis forces. Clearly, David Stirling’s belief ‘that a few men could inflict more damage – with less risk - than in a traditional attack’ was fully proven.

Although SAS Battle Ready is a perfectly readable and informative book, I do have reservations about it. Firstly, a quick glance at the book’s bibliography reveals that no primary research was done whatsoever. If Mr. Utton did conduct his own research but simply neglected to cite his sources, then I stand corrected. Nonetheless, the book appears to be largely a compendium of other writers’ works. Because of Dominic Utton’s economy of research, SAS Battle Ready has nothing new to tell us about the SAS that hasn’t been said before. I, personally, have never attempted to conduct any research on British special forces. However, ex-SAS veterans like Rusty Firmin and Robin Horsfall are no longer hard men to find. In fact, both men have their own websites and are easily contactable via LinkedIn.

The lack of any evidence of primary research brings me to my second question, criticism, or concern about the writing of SAS Battle Ready, and that is why bother? Surely, given the right inputs an AI (artificial intelligence) application like ChatGPT or Google’s Bard could have produced something similar. Of course, the obvious, rather cynical answer to my own question as to why write yet another book about the SAS is that they’re popular and likely to sell. The ex-SAS soldier turned prolific author Steven Mitchel (pen-name Andy McNab) is a veritable one-man publishing house, turning out over 30 fiction and non-fiction titles based on his time with the Regiment.

It is difficult to give an exact number as new books about the Special Air Service are constantly being published. However, it is safe to say that hundreds of books have been written about the SAS since the end of the Second World War. Andy McNab’s Bravo Two Zero (1993) and Immediate Action (1995) have both become international bestsellers. More recent books like SAS: Rogue Heroes - The Authorised Wartime History by Ben Macintyre (2016) have been adapted for television and spawned a plethora of films, TV documentaries, reality TV shows, podcasts, and computer games. Audiences seem to have an insatiable appetite for all things SAS related. Luckily for the Ministry of Defence (MOD), the Regiment’s Winged Dagger unit insignia and famous ‘Who Dares Wins’ motto is Crown copyright protected, which hopefully contributes to our dwindling defence budget, but I digress. Military history and the media and entertainment industries have always had a symbiotic relationship, and long may it continue. However, writing books about the SAS that have nothing new to say and simply rehash other authors’ works seem a little cynical and opportunistic.

I’m sure Dominic Utton’s SAS Battle Ready will sell, and the publisher will no doubt see a return on their investment. Overall, I cannot help feeling a bit cheated by the book’s lack of effort. Perhaps, whoever plays it safe also wins.

SAS Battle Ready by Dominic Utton is published by Michael O’Mara Books Ltd., 2023.

The British Army’s Occupation of Northwest Germany after May 1945

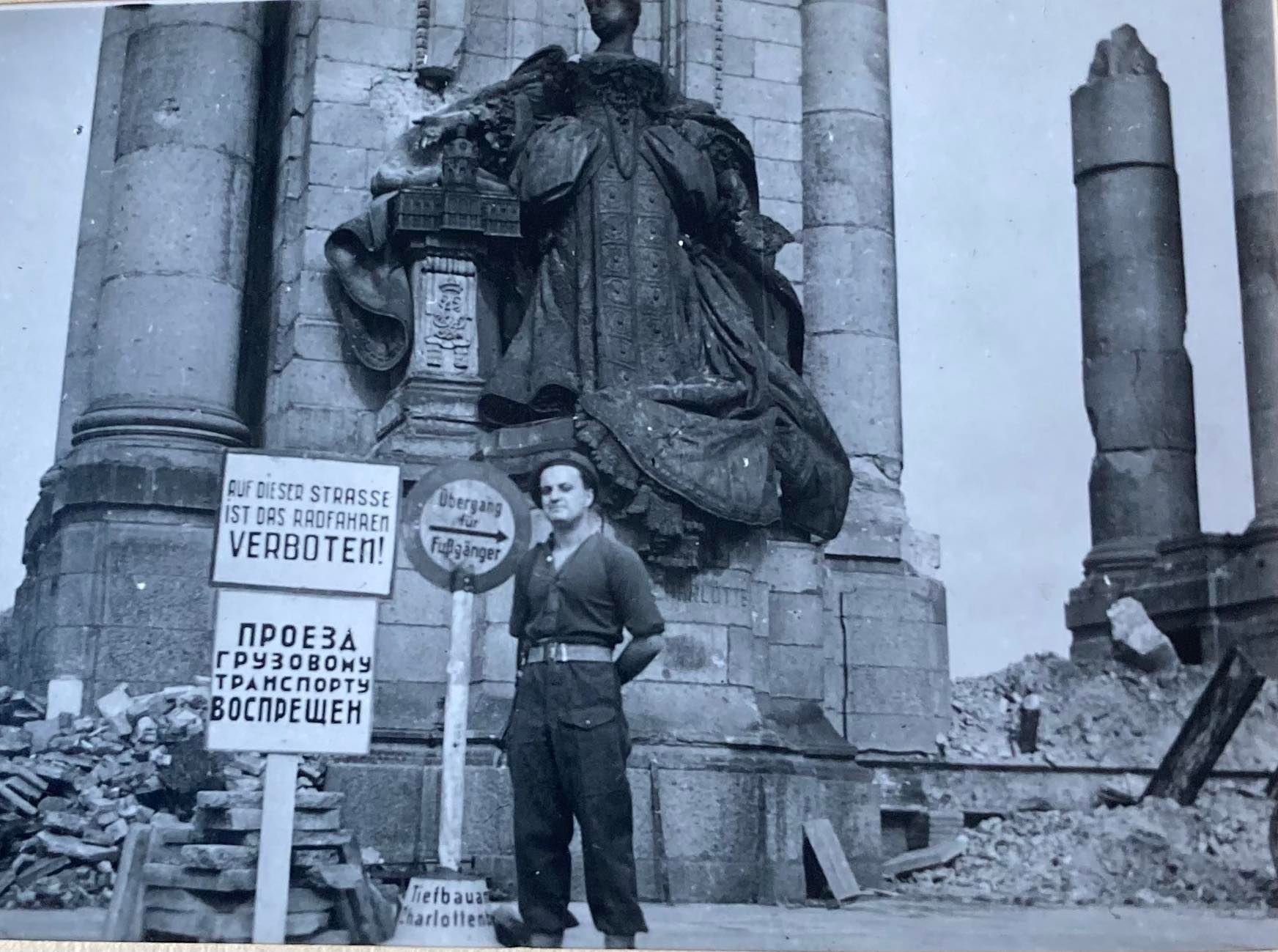

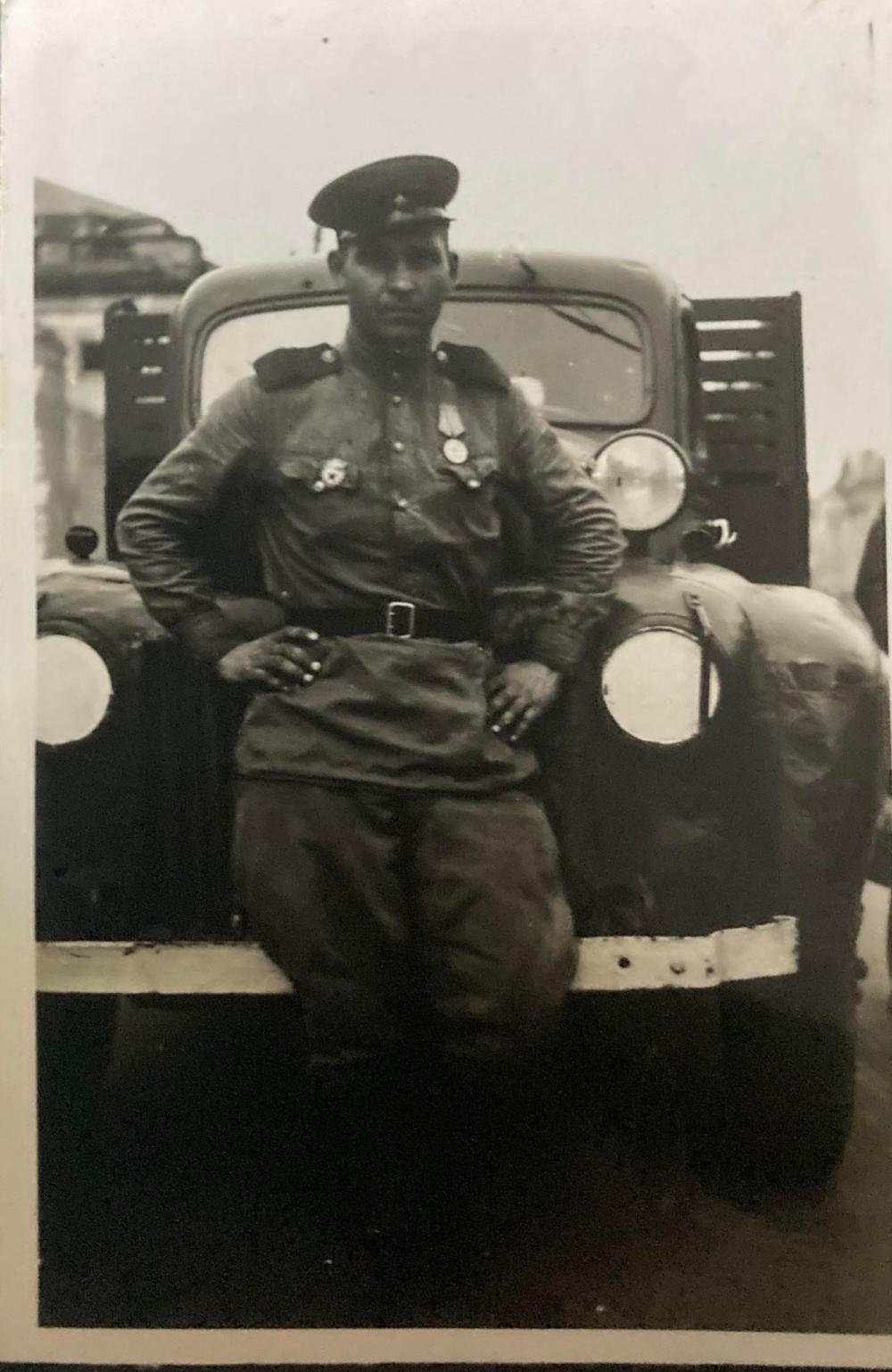

In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

After the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945, the victorious Allied powers divided the country into four occupation zones, each controlled by one of the four occupying powers - the United States, Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union. This division of Germany would mark the beginning of a new era for the country, as it faced a long and difficult process of reconstruction and democratization. In this article, we will focus on the British occupation of Germany after May 1945, the British Army's occupation of West Berlin, the Victory Parade of July 1945, and relations with the Soviets.

The British Occupation of Germany after May 1945

On 25 August 1945, Field Marshal Montgomery's 21st Army Group was renamed the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR). It was responsible for the occupation and administration of the British Zone in northwest Germany, including the cities of Hamburg and Bremen, assisted by the Control Commission Germany (CCG). The CCG took over aspects of local government, policing, housing and transport.

Their primary objective was to demilitarize and disarm the defeated German forces, as well as to dismantle the Nazi regime and bring war criminals to justice. The British forces, under the command of Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, faced a daunting task, as Germany was in a state of complete chaos and disarray.

One of the first challenges the British faced was dealing with the large numbers of displaced persons, refugees, and prisoners of war. The British Army, along with other Allied powers, established numerous displaced persons camps and worked to repatriate prisoners of war and refugees to their home countries. The British also faced the challenge of providing food and shelter to the German population, which was suffering from severe shortages of basic necessities such as food, fuel, and medicine. The BAOR mobilised former enemy soldiers into the German Civil Labour Organisation (GCLO), providing paid work and accommodation for over 50,000 Germans by late 1947.

The BAOR was also responsible for pursuing suspected war criminals in its zone of occupation. It established the British Army War Crimes Investigation Teams (WCIT) and was assisted by other units, including the Special Air Service (SAS). The most famous Nazi caught by the British was Heinrich Himmler, chief of the SS and one of the main architects of the Holocaust. He was arrested at a checkpoint and taken to an interrogation camp near Lüneburg. However, Himmler was able to escape prosecution for his crimes by committing suicide with a concealed cyanide pill. Political support for war crimes prosecutions soon declined as relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated. It soon became a political necessity for the Western powers to make friends with the Germans rather than prosecute them.

The British Sector of Berlin 1945

The British Army's occupation of the British sector of Berlin in 1945 was a key moment in the post-war history of Germany. Berlin, which was located deep within the Soviet-occupied zone of Germany, was divided into four sectors, with the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, and France each controlling a sector. The British sector was in the western part of the city.

The British Army faced numerous challenges in the occupation of Berlin. The city had been heavily bombed during the war, and many buildings were in ruins. The British Army worked to rebuild the city's infrastructure and provide basic services such as water, electricity, and sanitation.

Another major challenge faced by the British Army was dealing with the Soviet Red Army, which was stationed in and around Berlin. The relationship between the British and the Soviets was strained, with tensions running high over issues such as the repatriation of Soviet prisoners of war and the control of Berlin. The British Army, along with the other Allied powers, worked to maintain a delicate balance of power in the city, while also providing security and maintaining order.

The Victory Parade of July 1945

On 21 July 1945, the British held a victory parade through the ruins of Berlin to commemorate and celebrate the end of the Second World War. Around 10,000 troops of the British 7th Armoured Division, the famous 'Desert Rats', were paraded under review by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. On 7 September 1945, there was another parade featuring all the victorious Allies, but neither Montgomery nor U.S. General Dwight D Eisenhower attended. This gesture signified a deterioration in the relationship between the Allies, as differences in ideology between the West and the Soviet Union were becoming harder to ignore and the slide towards a Cold War had begun.

British Pathe News footage of the Berlin Victory Parade, 21 July 1945.

An Iron Curtain

Relations between the Western powers and the Soviet Union deteriorated immediately following the end of the war in Europe. The main sources of tension were the Soviet Union's unwillingness to allow democratic governments to emerge in Eastern Europe, and its desire to maintain a sphere of influence in the region. The Western powers, led by the United States, saw this as a threat to their own security and interests.

The Soviet Union's aggressive actions in the post-war period, including the establishment of communist governments in Poland, Hungary, and Czechoslovakia, fuelled Western fears of Soviet expansionism. The United States responded by implementing the Truman Doctrine, which committed the U.S. to support countries threatened by communism, and by providing economic and military aid to Western Europe through the Marshall Plan.

Tensions between the West and the Soviet Union reached a boiling point in 1947 when the Soviet Union refused to participate in the Marshall Plan and instead formed its own economic bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (COMECON). In 1948, the Soviet Union blockaded Berlin, prompting the Western powers to launch the Berlin Airlift to supply the city.

On March 5, 1946, former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "Iron Curtain" speech at Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri. In this speech, Churchill warned of the growing Soviet threat in Europe and called for a closer alliance between the United States and Great Britain to contain Soviet aggression. The speech marked a turning point in the post-war era and is considered a seminal moment in the Cold War.

In 1949, the three western occupation zones were merged to form the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany). The Soviets followed suit in October 1949 with the establishment of the German Democratic Republic (East Germany). In 1955, West Germany joined NATO and was encouraged to build a new military, the Bundeswehr. In response, the Communist states of Eastern Europe formed the Warsaw Pact.

Sources:

Photography/Images:

All photographs used to illustrate this article were taken by my relative George Trumpess who was stationed in Minden, Germany, and travelled regularly to Berlin during the summer of 1945.

The enduring importance of studying military history

This article explores the importance of military history and how it can shed light on the reasons behind conflicts, the motivations of those who took part, and the impact of technological innovations on warfare. It also discusses how the study of military history can broaden our understanding of the world and develop critical thinking and analytical skills.

The Second World War had a significant impact on the world we live in today. The study of military history has played a crucial role in understanding the causes and consequences of global conflict. This article explores the importance of military history and how it can shed light on the reasons behind conflicts, the motivations of those who took part, and the impact of technological innovations on warfare. It also discusses how the study of military history can broaden our understanding of the world and develop critical thinking and analytical skills.

The Second World War was a defining moment in human history, marking the end of the world as people knew it and paving the way for a new era of international relations, politics, and global economic power. It was a time of intense political, social and military upheaval, where nations and ideologies collided in a struggle for dominance and survival. Today, many years since the end of the war, the study of military history remains an important discipline, one that provides valuable insights into the causes and consequences of global conflict.

Lessons learned from a world at war

There are several reasons why the study of military history is important. First, military history helps to shed light on the reasons behind conflicts and the motivations of those who took part in them. This understanding can help to prevent similar conflicts from occurring in the future. For example, the lessons learned from the Second World War have helped to shape the modern world, including the establishment of the United Nations, the creation of international human rights laws and the promotion of democracy and free trade. However, on the first anniversary of the war in Ukraine, it is also tragically clear that the lessons of history do not prevent old enmities and new conflicts from happening.

Of course, military history can only teach us what we are willing to learn and does have practical applications that are relevant to the modern world. For instance, military history is used by policymakers, military planners and international organisations to inform their decisions and shape their strategies. Understanding the lessons of past conflicts can help to inform present and future military operations, improving the effectiveness of military interventions and reducing the risk of unintended consequences.

Technology and innovation

The study of military history can also provide insights into technological developments and innovations that have had an impact on warfare. For example, the Second World War saw the development of new weapons, tactics and technologies that changed the face of warfare forever. By studying the development and application of these technologies, military historians can help to inform future innovations and ensure that new technologies are used in the most effective and responsible manner possible.

The Second World War saw the development of many technologies that went on to transform post-war life.

The development of cryptography during the Second World War led to the creation of the first computers, which were used to decode enemy messages. The first electronic computers, such as the American ENIAC and British Colossus, were developed during the war and laid the foundation for the digital revolution that would transform post-war life. The use of computers in business, research, and everyday life has become ubiquitous, and the ability to process and store vast amounts of data has revolutionised every field of human endeavour.

Similarly, the development of jet engines during the war helped transform aviation. In 1949, the de Havilland DH.106 Comet became the world’s first commercial passenger jet. Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the commercial airline industry reached 38.9 million flights globally in 2019.1 The jet engine made air travel faster, more comfortable, and more accessible to the public. But emissions from aviation have also made a significant contribution to air pollution and possibly climate change.

The jet engine also had a profound impact on post-war military aviation, enabling supersonic flight and the development of fighter jets with unprecedented speed, stealth, agility and firepower. The impact of the jet engine on travel, commerce, and military power is still felt today. For example, it is believed that the use of western warplanes like the F-16 and Gripen fighter by the Ukrainian Air Force could prove decisive in the war against Russia. Of course, only time will tell.

Critical thinking and analytical skills

In addition to its practical applications, military history is also important in a more general sense, as it helps to broaden our understanding of the world. The study of military history provides a context for understanding the complex relationships between nations, and the motivations behind political, economic and military actions. This understanding can help to inform our understanding of the world today and the events that shape it.

Furthermore, military history is an important tool for teaching critical thinking, analytical skills and historical awareness. By studying military history, students can learn how to evaluate evidence, think critically about historical events, and understand the context in which they occurred. This knowledge can help to develop the skills necessary for a successful future, whether in the military, government, private sector, or academia.

In his 1961 paper, The Use and Abuse of Military History Michael Howard discusses the role of military history in the study of war and its use and abuse by politicians, military leaders, and the public.

Howard argues that military history is an essential tool for understanding the nature of war, but it is often misused for propaganda purposes. Military history should be studied objectively, without political bias, and used to inform policy decisions. However, politicians and military leaders often use selective historical examples to justify their actions, leading to a distorted understanding of history and potentially dangerous policies.

One of the key conclusions of the paper is that military history should be used to illuminate the realities of war, rather than to glorify it or justify particular policies. Howard emphasizes the importance of studying the social, economic, and political context of war, as well as military tactics and strategy. He argues that a more nuanced understanding of history can help prevent the mistakes of the past from being repeated in the present.

Overall, Howard's paper is a call for a more critical approach to the use of military history, both in academia and in the public sphere. It highlights the potential benefits and pitfalls of using history to inform policy decisions and stresses the importance of a clear-eyed understanding of the complexities of war.2

Certainly, I would agree with Howard’s premise that military history should be studied in breadth, depth and within the context of the times to try and gain an unbiased perspective of events. To the school pupil and casual observer, history might appear dusty, static and linear, but that is seldom the case. The study of history is a dynamic, interpretive, and iterative process that welcomes new viewpoints and encourages debate.

The utility of history as a military training aid

Operation Goodwood was a British offensive launched on July 18, 1944, during the Normandy Campaign. The operation involved a massive armoured and infantry assault against German forces in the Caen sector, with the aim of drawing German forces away from the American offensive, Operation Cobra, further west. The operation was supported by a massive aerial bombardment.

Despite the numerical superiority of the Allied forces, the operation met with mixed success. The British armoured units suffered heavy losses from German anti-tank guns, self-propelled (SP) guns and tanks, while the infantry made only limited gains. Nevertheless, the operation resulted in the destruction of many German tanks and artillery pieces but at a high cost in terms of Allied casualties. Immediately after the conclusion of Goodwood on 20 July 1944, controversy began about the operational intentions of the plan.

Today, Operation Goodwood continues to generate historical debate and controversy regarding its intentions and results. Subsequently, it has become a popular subject for writers, journalists, historians, and military theorists. In 1980, General Sir William Scotter proposed that German defensive tactics used at Goodwood might provide a template for NATO forces to repel a Soviet armoured offensive in northwest Europe. General Scotter’s proposition suggested that the German defensive strategy during Operation Goodwood, which involved using a combination of anti-tank guns, minefields, and concealed infantry positions to halt enemy armour, could be effective against Soviet tank formations. The idea was that NATO forces, like the Germans, could use a combination of conventional and unconventional tactics to slow down and disrupt Soviet tank offensives. This strategy was seen as especially useful for defending key chokepoints and urban areas.3

In 1982, Charles Dick sought to refute the so-called ‘Goodwood concept.’ Dick argued against this proposition, pointing out that the Soviet army had evolved since the Second World War and had developed new tactics and weapons systems. He argued that a strategy based solely on the German model would be insufficient to defeat a modern Soviet army. Moreover, it can be argued that the German defensive strategy was ultimately unsuccessful during Operation Goodwood. After all, the Allies were still able to achieve limited success and write down tanks, troops, and equipment that the Germans could not afford to lose or easily replace. Nevertheless, a generation of British Army officers visited the Goodwood battlefield, escorted by key protagonists such as Major-General Roberts, commander of the 11th Armoured Division, and Colonel Han Von Luck, 21st Panzer Division, and quite possibly learned the wrong lessons from a study of the operation.4

According to the U.S. Army’s Centre of Military History, staff rides (a combination of battlefield tours and exercises) represent a unique and persuasive method of conveying the lessons of the past to the present-day Army leadership for current application. Properly conducted, these exercises bring to life, on the very terrain where historic encounters took place, examples, applicable today as in the past, of leadership, tactics and strategy, communications, use of terrain, and, above all, the psychology of men in battle. It is true that staff rides are widely used by military organisations across the globe as a teaching aid, but not universally.5

The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) reject the type of learning-from-history model typified by the staff ride. The IDF prefers to rely on practice and its own experience to prepare for future operations rather than the study of history. In The Staff Ride: A Sceptical Assessment, Anthony King argues that staff rides are of limited practical utility for preparing military leaders to face the unique challenges and stresses of combat. Instead, he contends that staff rides are primarily a social networking exercise, which helps unify the officer corps and create personal bonds between them. Secondly, he believes that staff rides also help fortify commanders when faced with making difficult decisions, knowing that their predecessors experienced similar challenges.6

As every conflict is a unique, never to be repeated event, the staff ride might be of limited practical use to the fledgling military commander. Nevertheless, the study of military history highlights the many similarities as well as the differences between conflicts, which in turn can provide useful templates to help inform and fortify the decision-making of tomorrow’s commanders. The British Army believes that military history can provide examples of courage, leadership and resilience that can be applied in a variety of contexts. However, it is also clear that we should be critical of how we choose to interpret historical events and the lessons we believe they teach us.

A deeper understanding of identity

The study of military history can help individuals develop a deeper understanding of their nation's identity and place in the world. In the United Kingdom, for example, military history is seen as an important part of national identity and heritage. According to The Royal British Legion studying military history can help individuals understand the significance of the role the Armed Forces have played in shaping the nation.

Military history also helps to preserve the memory of those who served and died in wars. The Second World War was one of the deadliest conflicts in human history, with millions of lives lost. By studying its history, we can honour the sacrifices of those who fought and died and ensure that their memory is not forgotten.

Studying genealogy, which is the study of family ancestry and lineage, can help someone gain a greater sense of identity by providing them with a deeper understanding of their family history and cultural heritage. Learning about one's ancestors, traditions, values, and experiences, can help individuals connect with their roots and develop a sense of belonging to a larger family community. By exploring their family history, individuals may discover inspiring stories of military service, resilience, determination, and triumph over adversity, which can serve as a source of inspiration and motivation. Overall, studying genealogy can help individuals better understand and appreciate their identity and place in the world.

In conclusion, the study of military history remains an important discipline that has both practical and academic applications. By studying military history, we can learn the lessons of past conflicts, inform future military operations and shape our understanding of the world. Whether we are students, policymakers, military planners or simply interested citizens, the study of military history provides us with a valuable tool for understanding the world and ensuring a safer, more peaceful future.

The study of military history can also teach us to be more critical and analytical and question our assumptions and biases because it provides us with a unique perspective on the past and the present. By examining historical events and military strategies, we can gain a deeper understanding of how decisions were made, what factors influenced them, and what the consequences were. This can help us develop critical thinking skills, as we learn to evaluate evidence, weigh different perspectives, and analyse complex situations.

Furthermore, studying military history can expose us to a range of different cultural and political perspectives, allowing us to see how biases and assumptions can impact decision-making. By understanding the context and motivations behind historical events, we can develop a more nuanced and sophisticated understanding of the world and our place in it. This can help us become more empathetic and open-minded, as we learn to appreciate different viewpoints and challenge our own assumptions and biases.

Overall, the study of military history can help us become more critical and analytical thinkers, better equipped to navigate the complexities of the modern world and make informed decisions based on a deeper understanding of the past.

Sources:

1. Number of flights performed by the global airline industry from 2004 to 2022 (2023), Statista.com, <https://www.statista.com/statistics/564769/airline-industry-number-of-flights/> [accessed 20 February 2023].

2. Michael Howard, ‘The Use and Abuse of Military History,’ Parameters 11, no. 1 (1981), doi:10.55540/0031-1723.1251.

3. General Sir William Scotter, ‘A Role for Non-Mechanised Infantry’, The RUSI Journal, 125.4 (1980), 59–62.

4. Charles J Dick, ‘The Goodwood Concept - Situating the Appreciation’, The RUSI Journal, 127.1 (1982), 22–28.

5. CMH Staff Rides, U.S. Army Center of Military History, <https://history.army.mil/staffRides/index.html> [accessed 28 February 2023].

6. Anthony King, ‘The Staff Ride: A Sceptical Assessment’, ARES& ATHENA Applied History 14, Centre for Historical Analysis and Conflict Research (CHACR), (2019), 18-21.